Introduction

Implant dentistry is a treatment modality widely used in daily practice for fully and partially edentulous patients to improve masticatory function and quality of life. This therapy offers not only significant functional and biologic advantages for many patients when compared with conventional fixed or removable prostheses, but also yields excellent long-term results, with success and survival rates above 95% and a low risk of complications. I would say that the main objectives of implant therapy are to achieve successful treatment outcomes with high predictability and good long-term stability, and to have a low risk of complications during healing and follow-up period.

The growing demand to replace missing teeth not only by functional but also esthetically pleasing implant-supported restorations has become an important challenge. The development of new implant designs and surface modifications allows new treatment approaches with reduced overall treatment times and immediate restorations, broadening the indications for dental implants. However, with their increased use, more complications have occurred.

Regarding implant complications, some of these situations require removal of the implant. What I see in daily practice is that the majority of the complications are related to:

- Implant malpositioning

- Biological complications

- Mechanical complications

The objective of this article is to share my experience regarding the criteria for explantation of dental implants.

Criteria for explantation of dental implants

According to the literature as well as my own experience, implant failures can be described as early or late failures. Early implant failures can have multiple causes, that is, lack of primary stability, contamination of the site or the implant during surgery, overheating of the bone during preparation of the implant site or healing disturbances. In this context, implants are clinically mobile and therefore easy to remove.

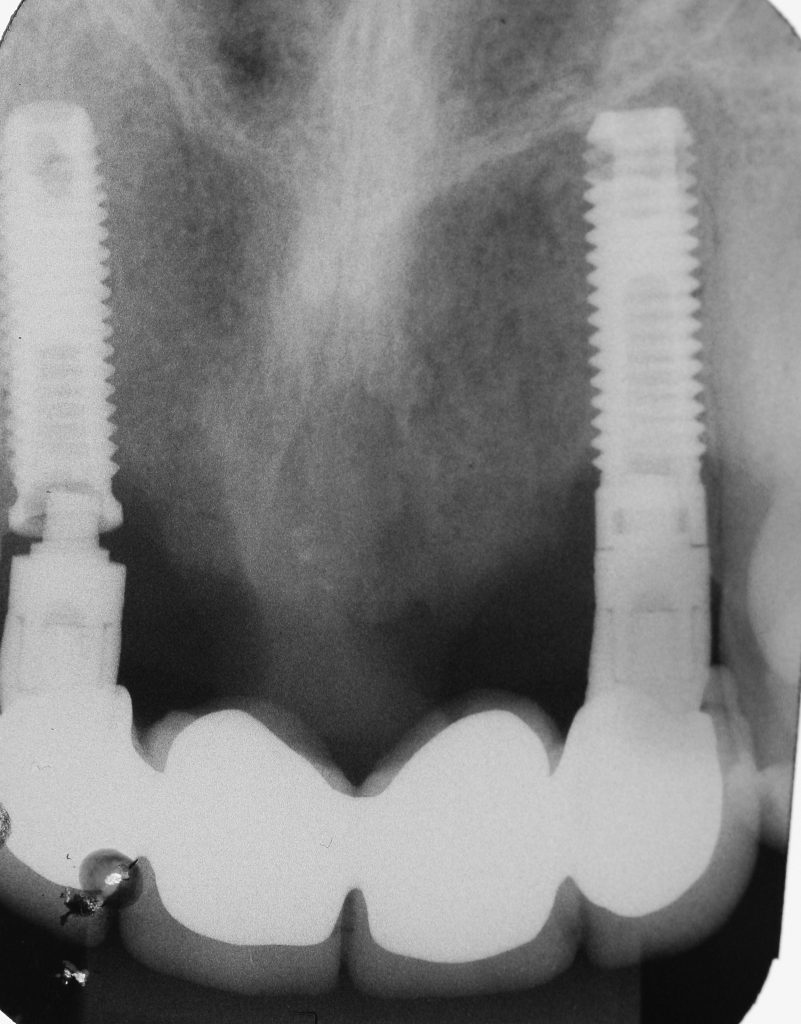

In my opinion, the challenging situations are related to the late implant failures, because sometimes the implants are fully osseointegrated and the removal of the fixture is not an easy task. This type of failure is mainly due to biological, mechanical or esthetic reasons (malpositioned implants/failed restorations). That means, bone loss due to peri-implantitis, extreme malpositioning or implant fractures are the most prevalent. Different methods of implant removal have been described in the literature so far including the use of counter-torque ratchet, piezosurgery, high-speed burs, elevators, forceps, trephine burs and laser surgery.

Malpositioned implants

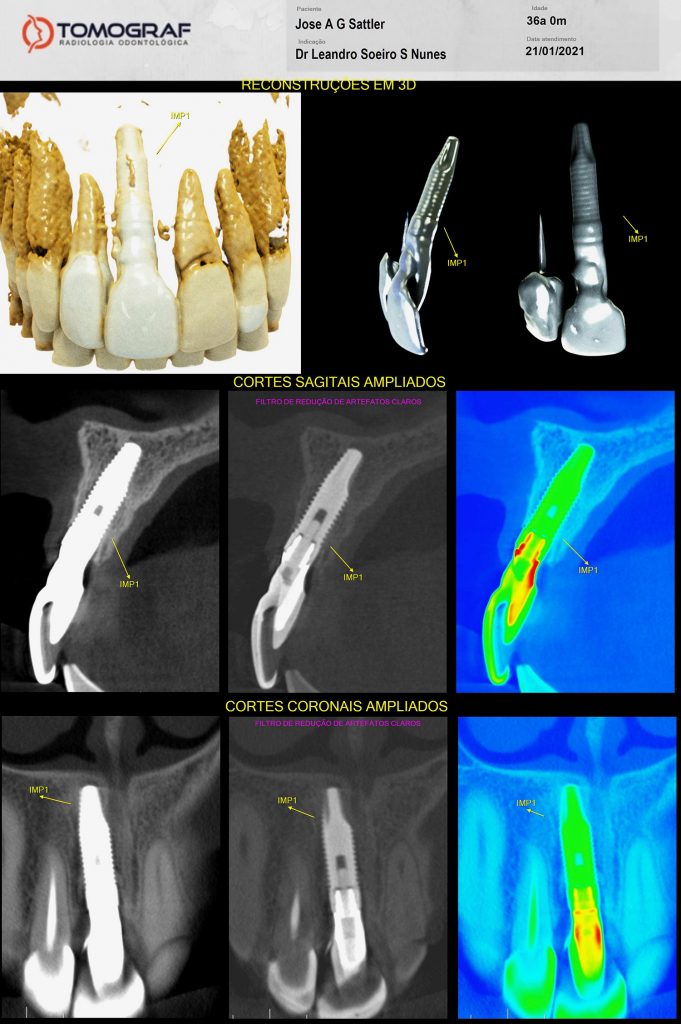

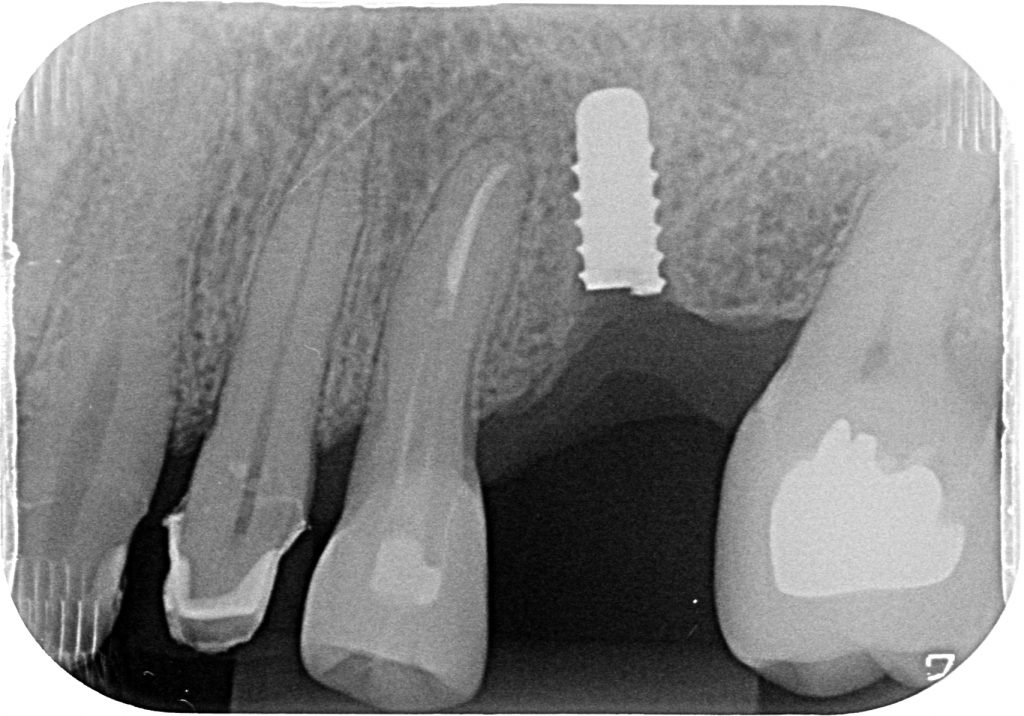

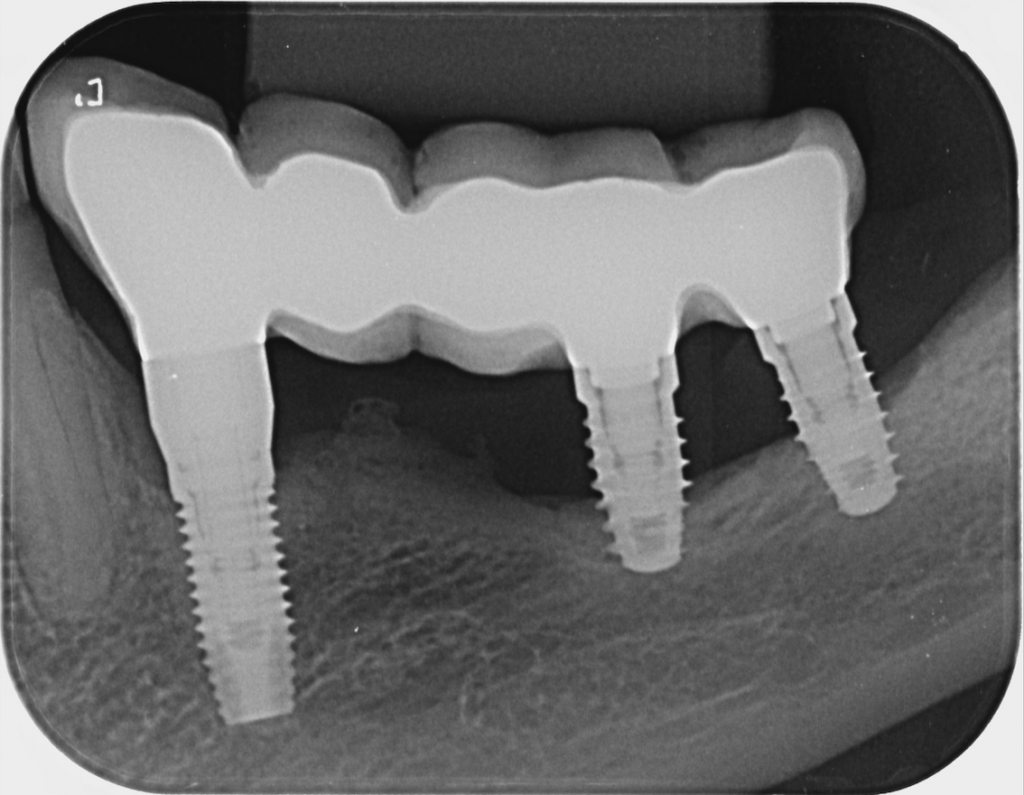

Dental implants can be malpositioned as a consequence of poor treatment planning, inaccurate surgical execution, different levels of surgical experience, restricted mouth opening or losing orientation during surgery. An incorrectly positioned implant (location, inclination, etc.) may impede adequate prosthetic rehabilitation in many cases (Fig. 1). What I have seen in daily practice is that biomechanical problems due to the wrong occlusal force axis, an inacceptable esthetic appearance, or difficulties in maintaining proper hygiene may be the consequence of malpositioned implants and, therefore, these implants have to be removed.

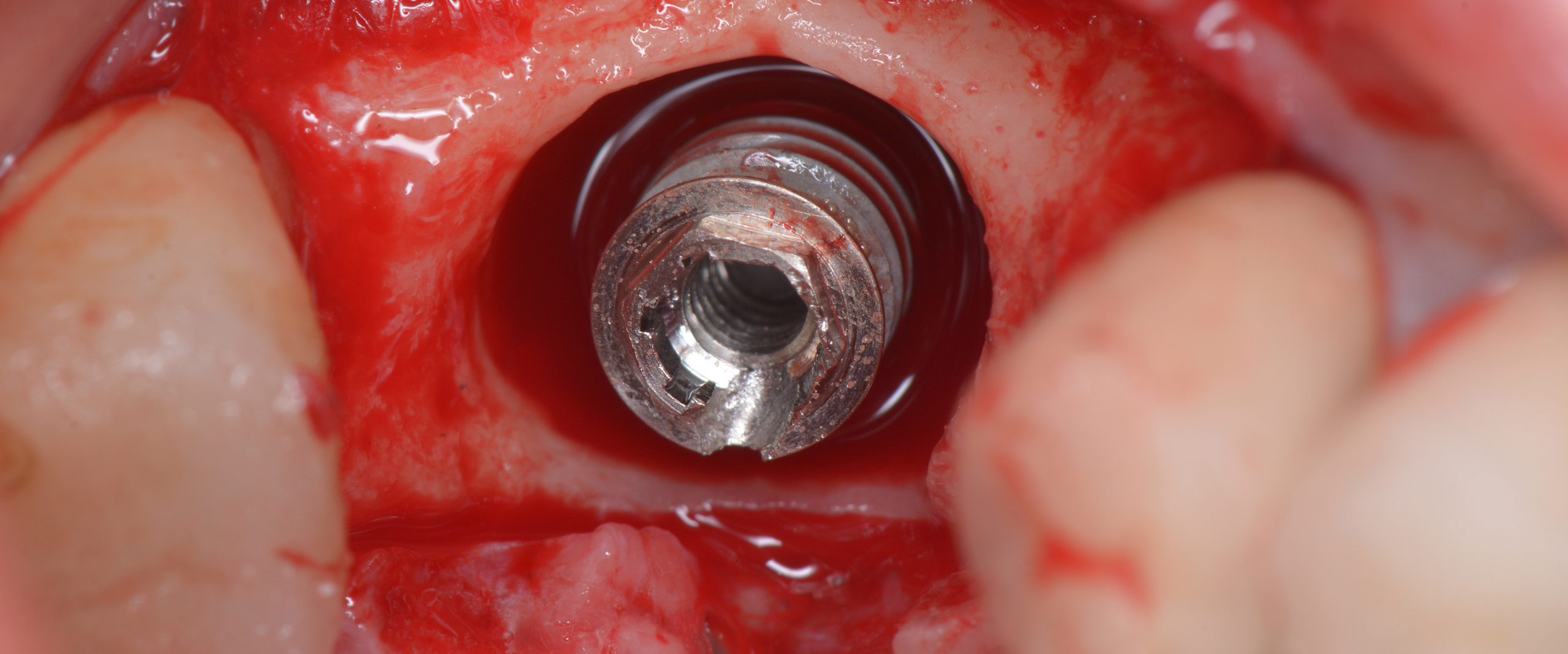

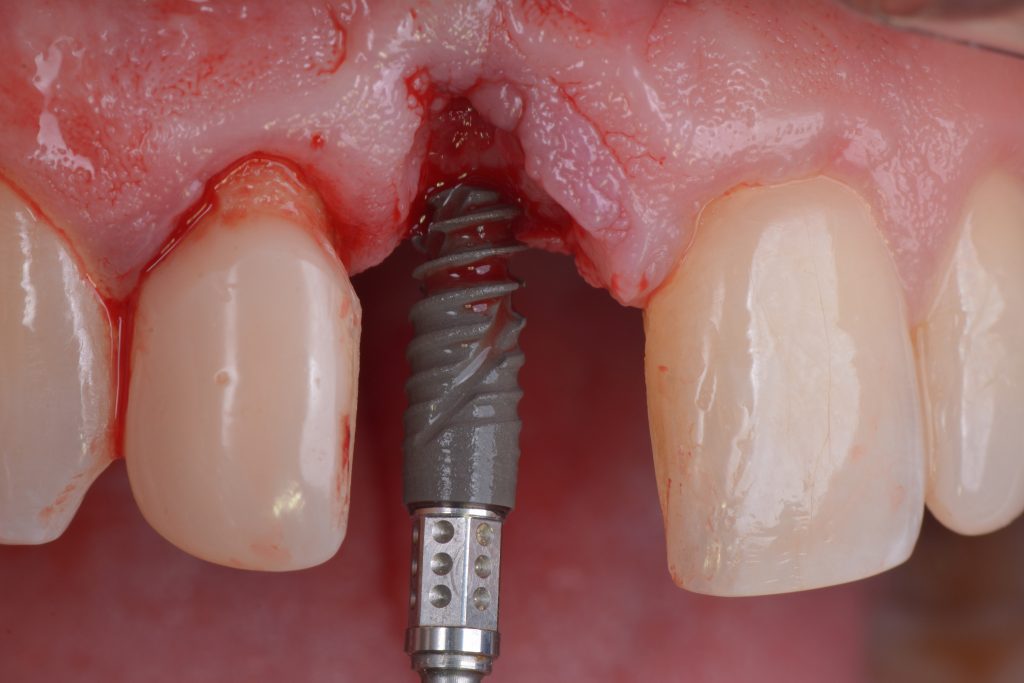

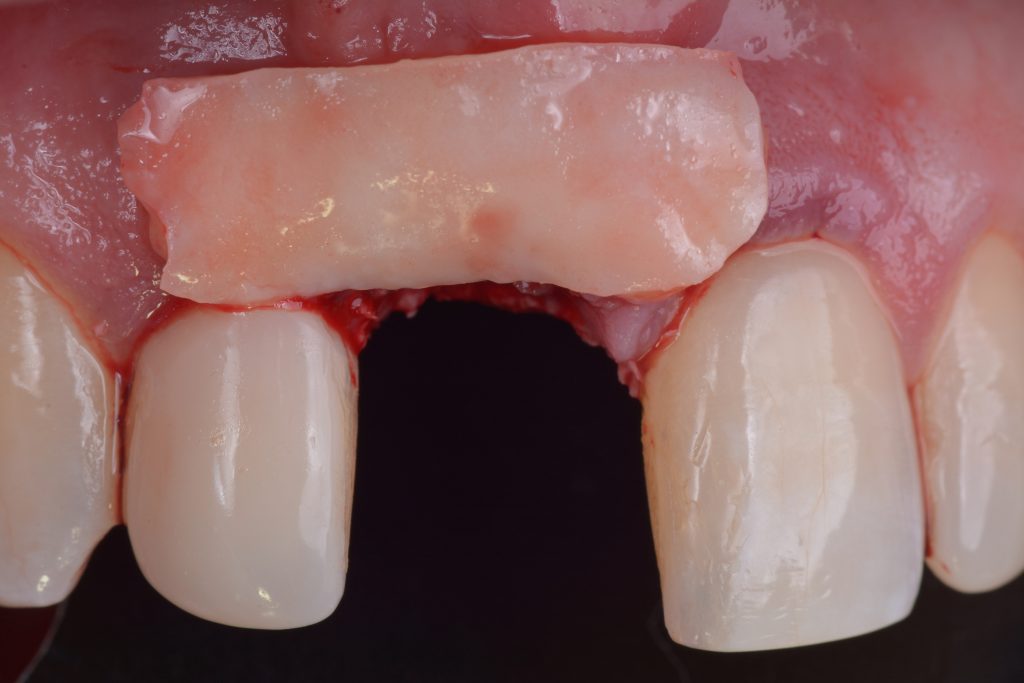

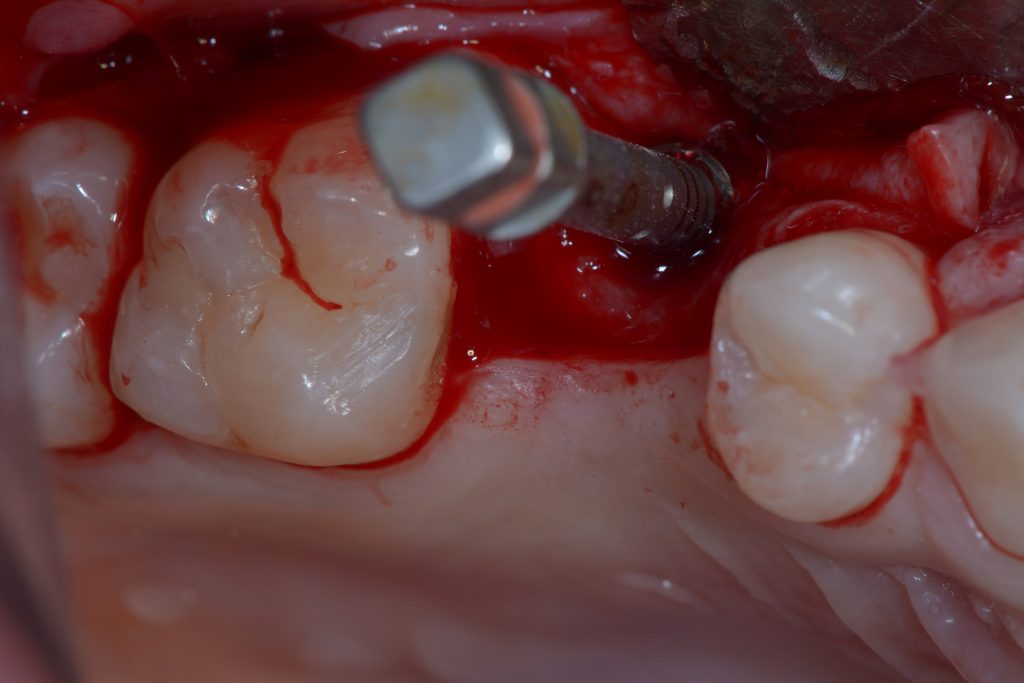

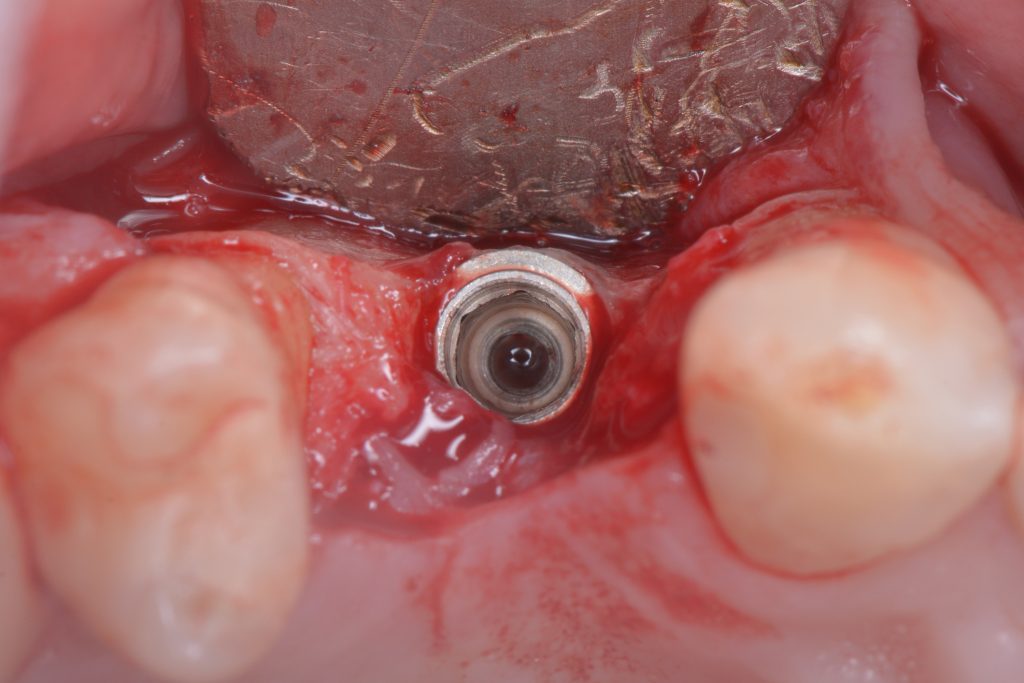

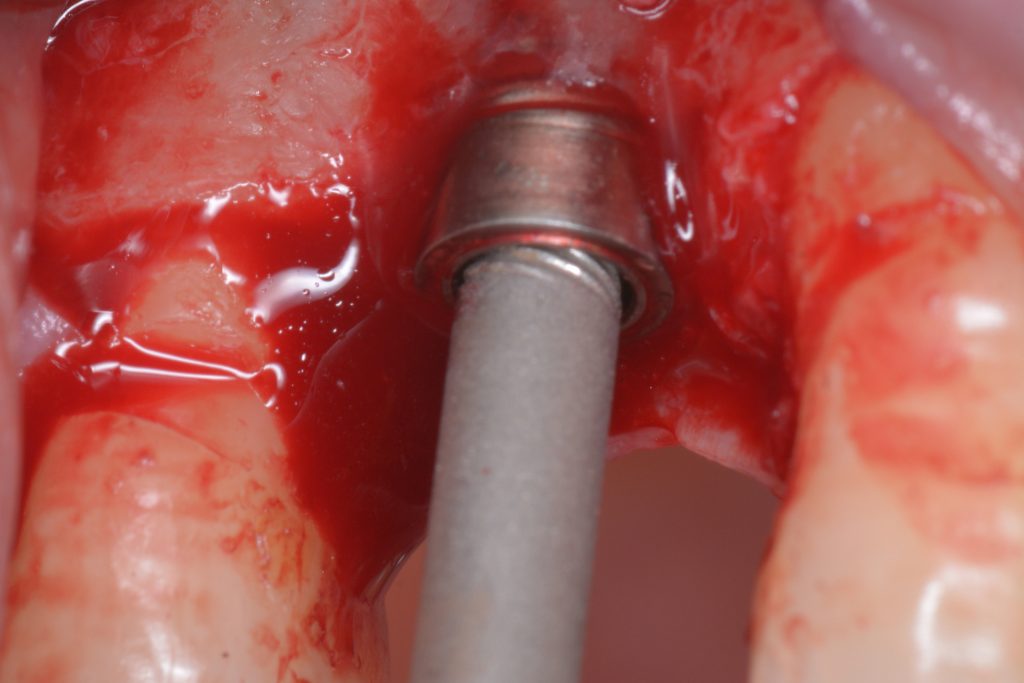

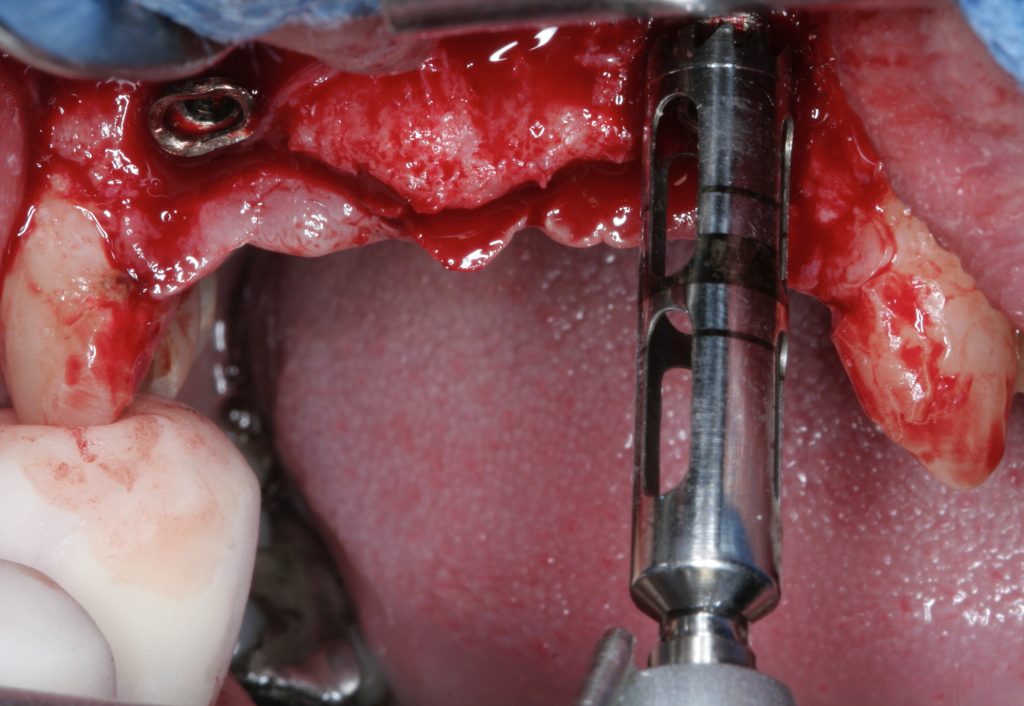

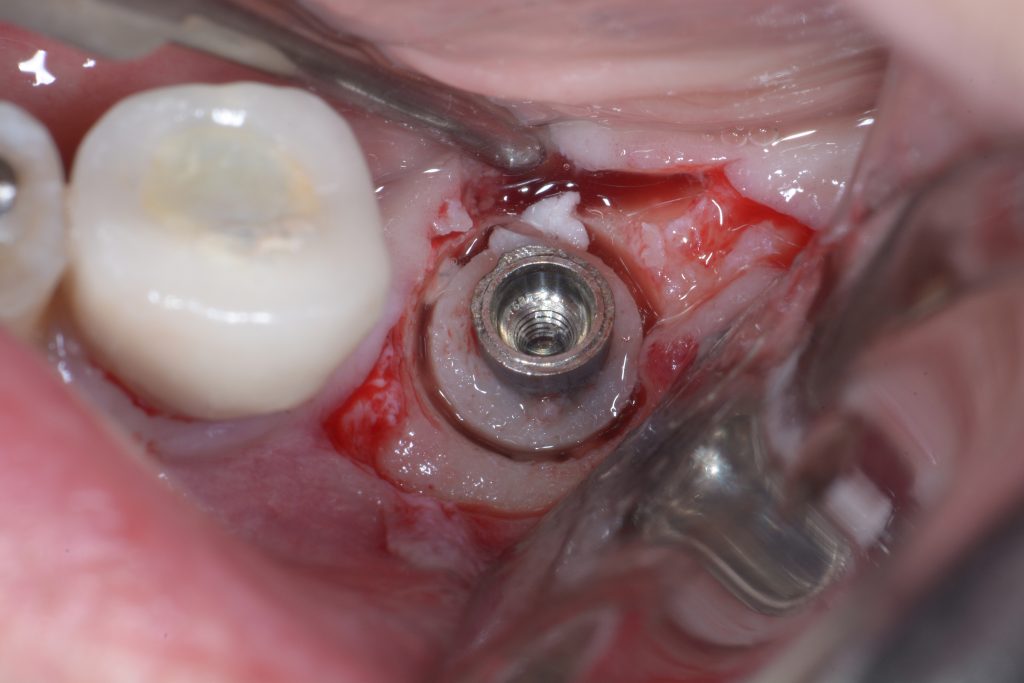

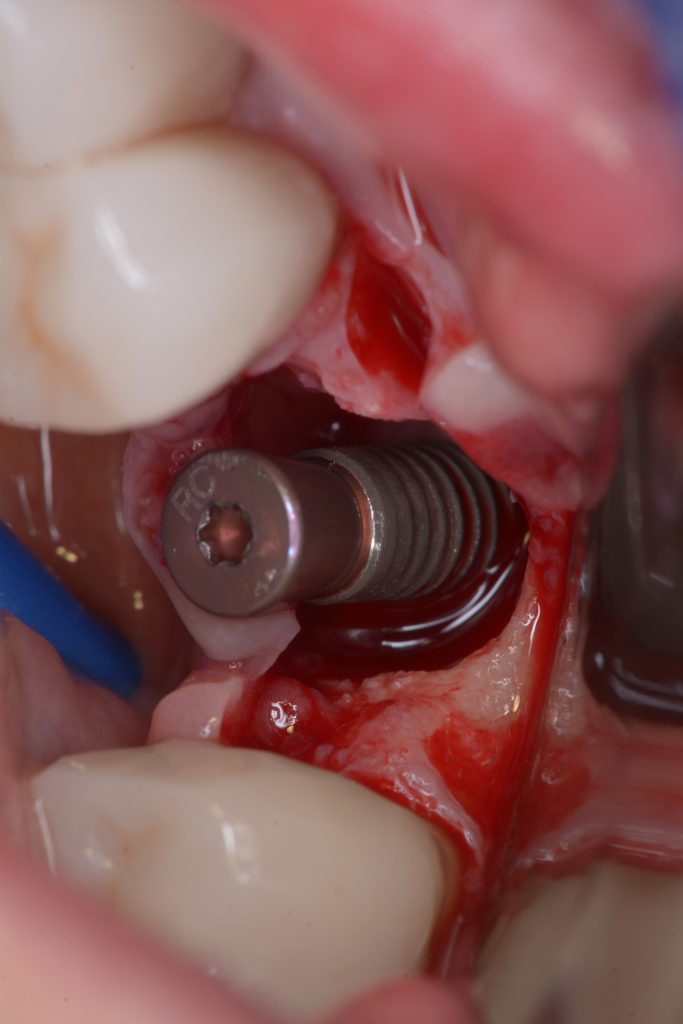

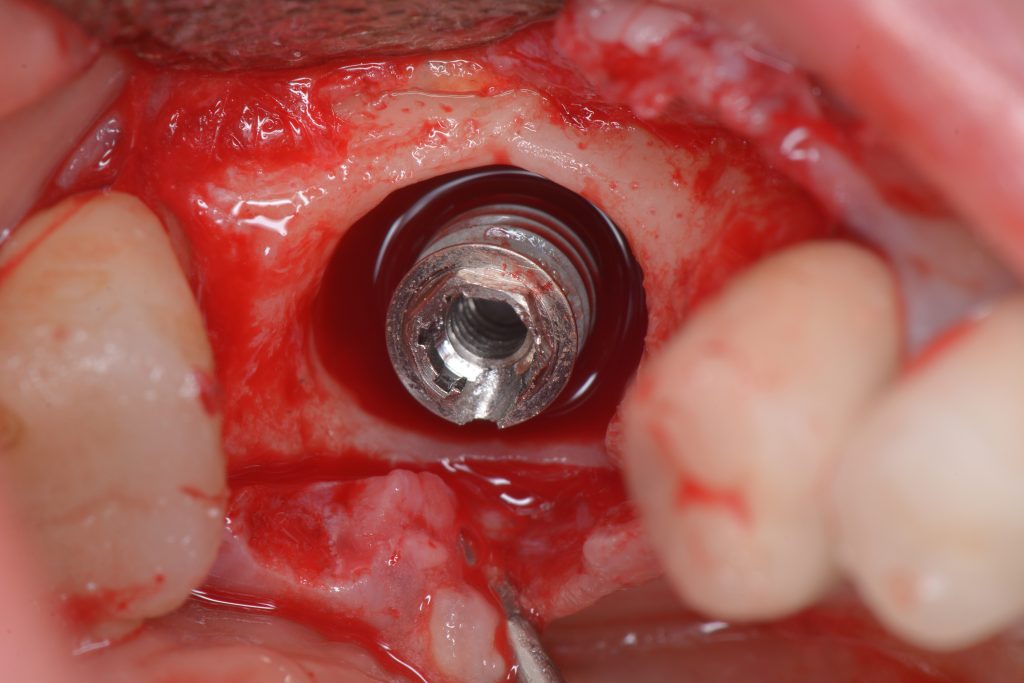

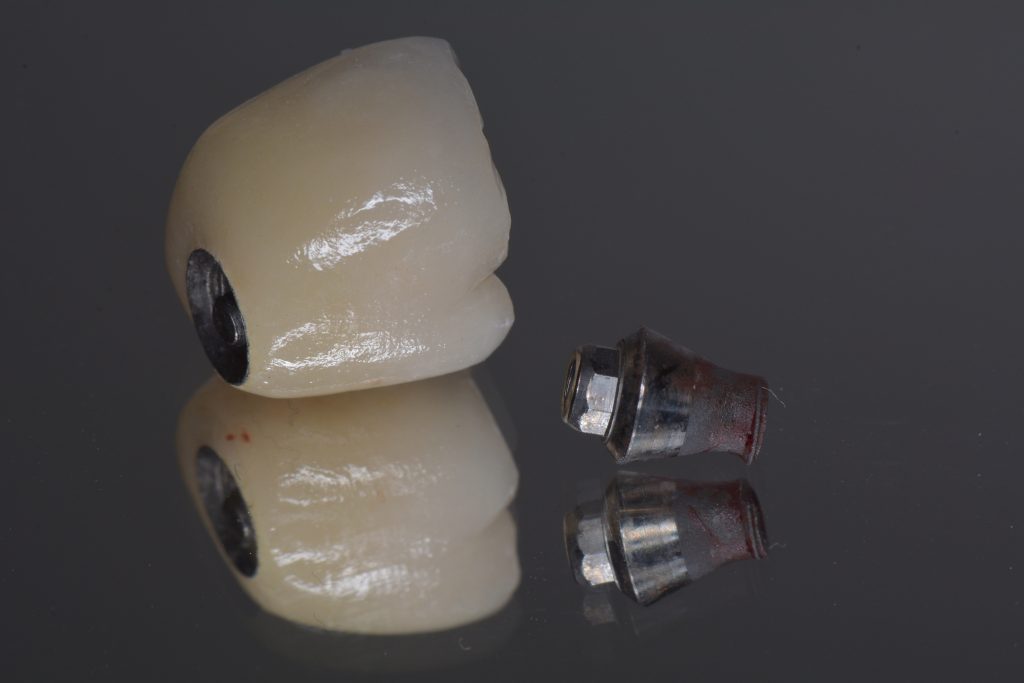

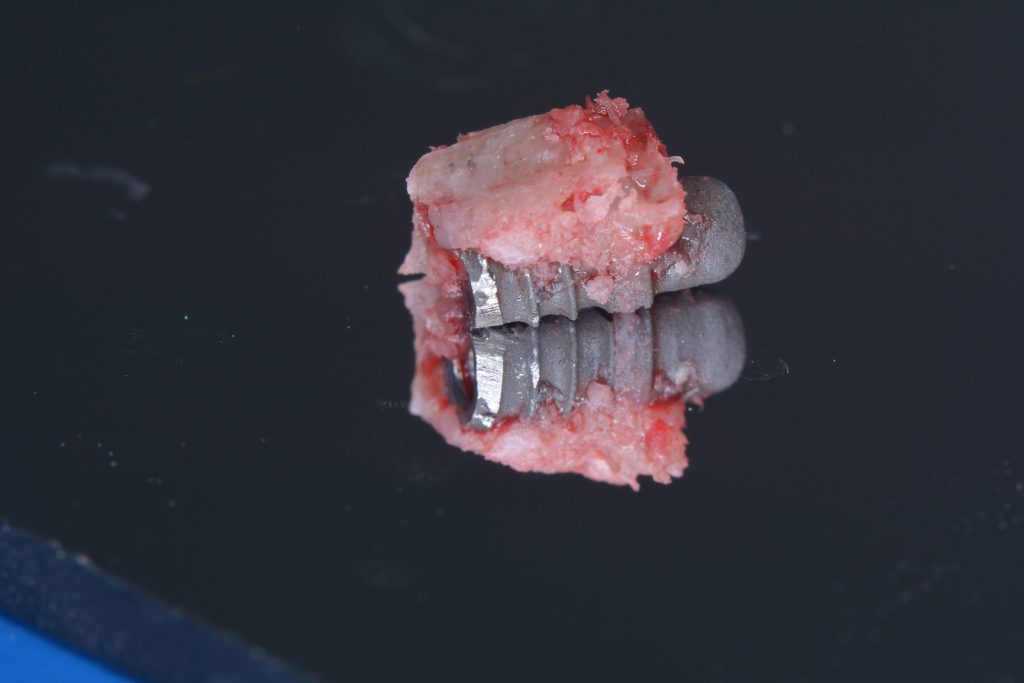

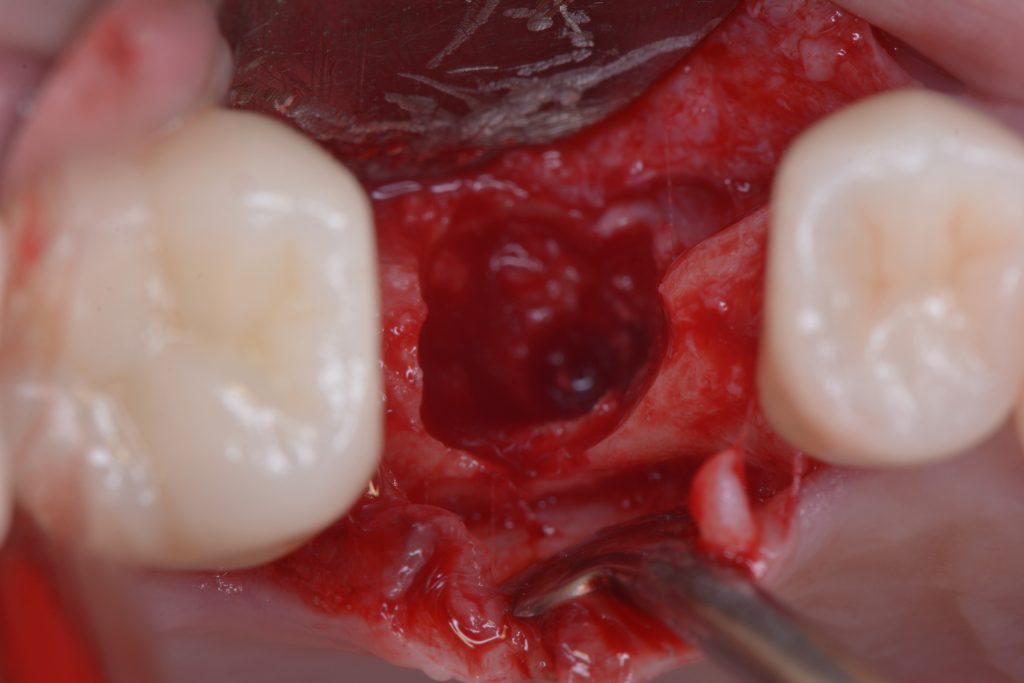

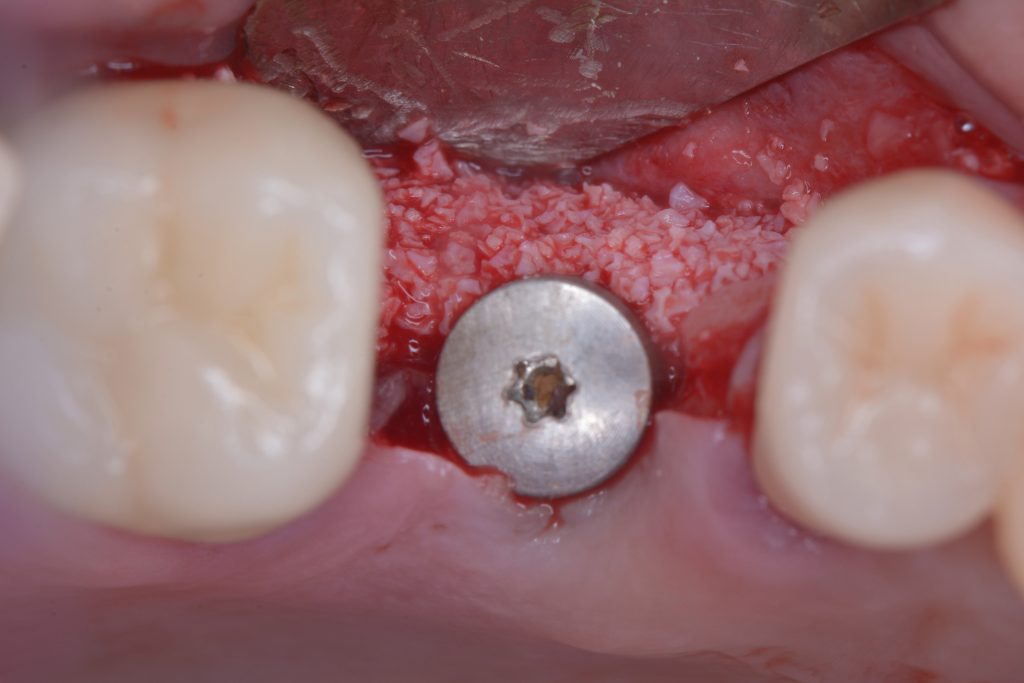

Usually, the removal of these implants is associated with damage to the hard and soft tissue around the implant. The methods used to remove the implant can also increase the damage, and the decision to use the right technique is very important, in my opinion. The least invasive techniques to remove malpositioned implants are the use of counter-torque (Fig. 2) and implant retrievers (Fig. 3). These approaches avoid additional bone loss, since the instruments are connected directly to the implant and do not create undesirable effects in the marginal bone. The use of forceps (Fig. 4) can be acceptable if there is previous marginal bone loss and the forceps are able to grab the implant without additional bone removal. The movement of the forceps must avoid significant bone luxation. So the implant must always be unscrewed and the forceps act as a screwdriver. The use of burs and trephine (Fig. 5) usually increases bone loss and requires immediate or late advanced bone regeneration to allow placement of another implant (Fig. 6). These approaches must be your last option, which means that other options must be tried before the use of burs and trephine. When using burs, it is advisable to remove part of the buccal bone to create a path to explantation. With the burs, elevators and forceps are normally used to remove the implants, which need some space between the bone and the implant to apply it properly. So, there is a need to increase the bone loss around the cervical part of the implant to allow explantation with these tools.

Biological complications

Despite the favorable clinical results, peri-implantitis (Figs 7-8) has become one of the major biological complications and represents the main reason for late implant failure. Professional boards of periodontists suggest that the incidence of biologic complications, and more specifically of peri-implantitis, may be up to 50%, which, in my opinion, is very worrying. I have also seen an increase in peri-implant mucosal recession around osseointegrated implants in function. Several factors, such as the thickness of hard and soft tissues surrounding the osseointegrated implant, incorrect implant positioning and/or the quality of prosthetic restorations, appear to play a role in the etiology of mucosal recessions. Excess cement on cement-retained restorations is another common cause of peri-implantitis and the clinician must pay strict attention during cement removal to avoid this type of complication.

The decision to remove an implant that presents peri-implantitis should be based on the presence of mobility, amount of bone loss, predictability of treatment outcome, prosthesis design and patient’s preference. According to the literature, and also based on my clinical experience as an oral surgeon, a mobile implant has to be removed. The loss of osseointegration due to infection around the implant is a condition that hinders the maintenance and treatment of the affected implant. Some studies have suggested that explantation is also indicated when ongoing bone loss exceeds more than half of the implant length. However, in my point of view, this indication to perform an implant removal needs to be associated with other factors, such as recurrent infection, persistent suppuration and failure of previous peri-implantitis treatment. If this implant is in a position that is strategically important to the supported prosthesis or if the supported restoration is esthetically satisfactory, saving and keeping the implant may be more prudent (Fig. 9).

The esthetics of the implant involved also represent an important aspect. If the treatment outcome is affected by the disease and the patient is not happy with this outcome, we have to discuss the risks and benefits of all the treatment options before a decision is reached. In my opinion, the removal of an implant due to poor esthetics caused by peri-implantitis is quite acceptable. So, the patient’s wishes need to be respected and the aim of our approaches need to converge with these expectations.

Mechanical complications

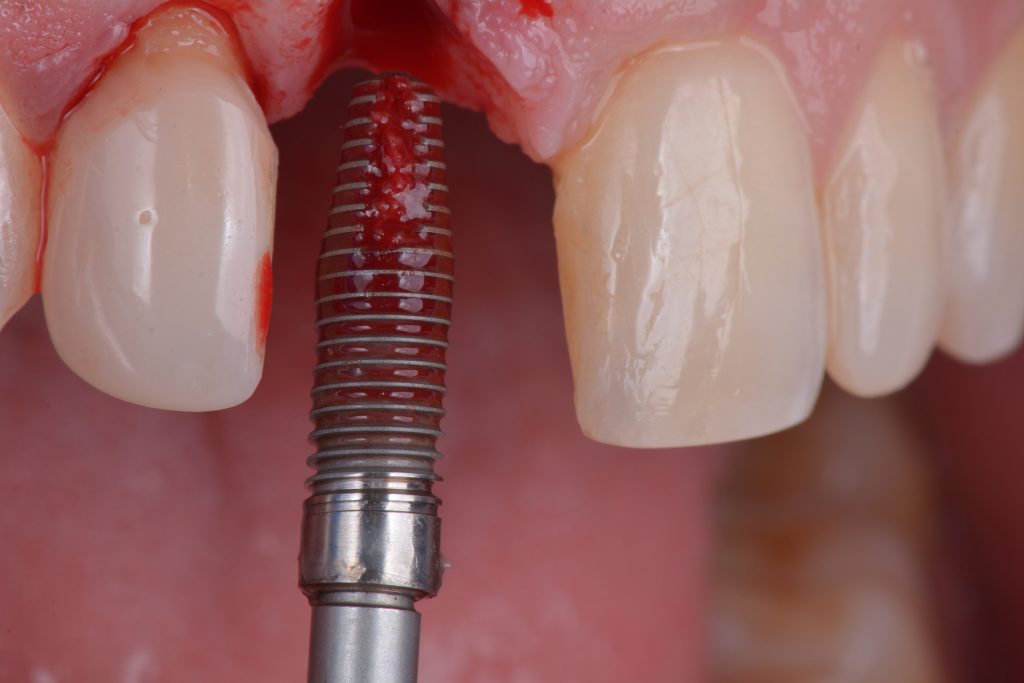

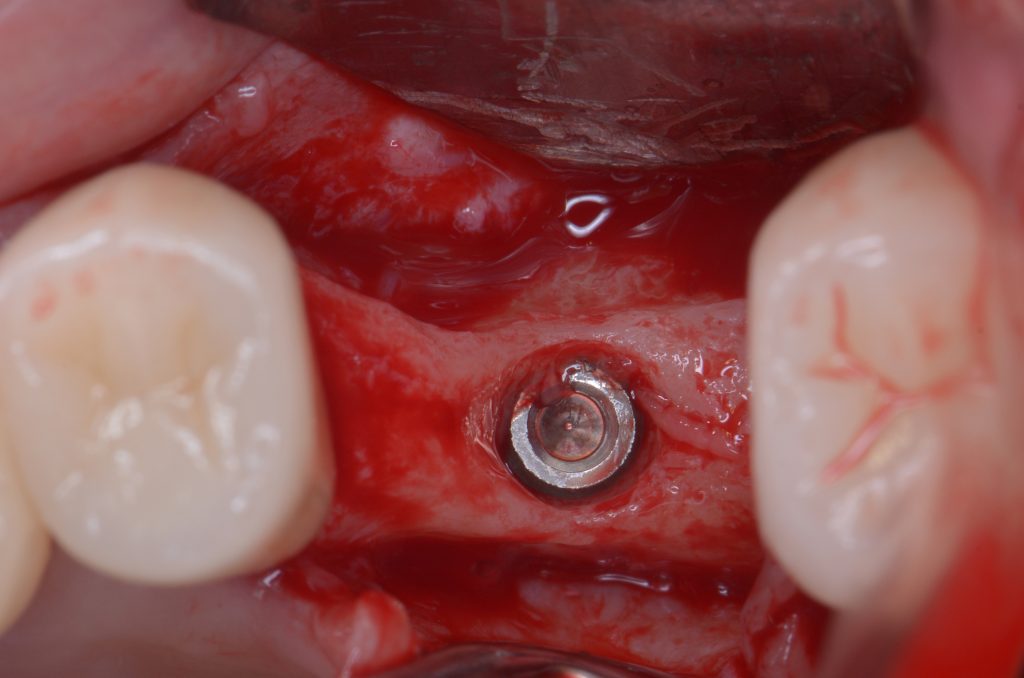

The prevalence of implant fractures is quite low, however a risk seems to exist especially in the molar region. If there is a possibility to replace the implant immediately, I would do it, especially in the case of mechanical failures, where there is no contamination associated with the site (Muroff 2003; Gealh et al. 2011) (Fig. 10).

The possible causes include bruxism, large occlusal forces, mechanical trauma, reduced implant diameters, material fatigue, and advanced bone loss leading to reduced mechanical support around the implant. Besides that, there are some reports in the literature showing that the risk of fracture increases over the lifetime of an implant.

The development of new alloys, such as RoxolidTM from Straumann, has allowed higher mechanical strength even in reduced diameter implants. These improvements in the fixtures have broadened the use of narrow diameter implants, without increasing the risk of implant fractures (Yaltirik et al. 2011; Müller et al. 2015). According to my observations, these implants can reduce the amount of bone augmentation needed in some cases, but it’s crucial that the implant is placed in the correct 3D position with enough surrounding bone and a proper amount of soft tissue to avoid biological and esthetic complications.

Conclusions and clinical recommendations

So, according to my observations, my clinical experience and the literature, the removal of an implant is a traumatic situation for the patient and also for the professional. In order to avoid it, correct implant planning, adequate implant placement and a maintenance program are mandatory.

If the removal of the implant is indicated, the use of counter-torque ratchet technique and retrievers represent the least traumatic techniques and should be your first attempt. After implant removal, it is important to create adequate conditions for new implant placement or to replace the implant immediately. In my opinion these procedures always have to be associated with bone and soft tissue regeneration, and advanced surgeries must be performed by skilled surgeons, because these sites are tricky and demanding.

My clinical recommendations are to treat the hard and soft tissue properly during implant removal and replace the failed implant as soon as possible using correct planning and suitable surgery/rehabilitation techniques.

More on this topic can be found on iti.org: