Abstract

Periodontal tissue phenotypes have been recently defined as the combination of gingival phenotype (GP) – earlier reported mainly as the gingival biotype – and bone morphotype. The main focus of this summary is to describe the GP as consisting of gingival thickness (GT) and gingival width (GW). GP has not only been investigated regarding its correlation with, for example, tooth shape, papilla height or buccal bone plate characteristics, but more importantly with regard to its impact on periodontal, implant, prosthetic and orthodontic treatment outcomes. Especially in the anterior segment, GP assessment before implant placement, particularly for immediate implants, is pivotal for esthetic but also for long-term stable results. Therefore, a standardized, reliable and easy-to-use method to assess the GP is warranted. Visibility of a periodontal probe inserted into the gingival sulcus seems the most appropriate approach: either the probe shines through the gingiva, reflecting a thin GP or the probe is not visible, hence, the GP is thick. Unfortunately, this dichotomous classification has two issues: 1) GP is a function of GT, hence, assessment in the intermediate area between thin versus thick might be challenging; 2) very thin/high risk cases as well as very thick/low risk cases cannot be identified. These observations led to the idea and development of a modified periodontal probe to enable GP classification into thin, moderate and thick phenotypes based on probe transparency as also described within the ITI SAC Classification Tool.

Phenotype assessment

The term “biotype” describes a group of organs sharing a specific genotype. The term “phenotype”, however, refers to the visible properties of an organism defined by the interaction of genetic determination – including the biotype – and environmental influences (Oxford, 2019). While the phenotype might change over time or be modified by surgical interventions, for instance, this may not necessarily apply to the biotype. However, both terms have been used synonymously when describing different entities of gingival thickness and other characteristics.

According to the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions (Jepsen et al., 2018) the term periodontal phenotype was proposed to be used primarily in order to simplify the nomenclature. It consists of the gingival phenotype (GP) and the bone morphotype. Furthermore, it is a combination of gingival thickness (GT) and width of keratinized gingiva (GW). As mentioned above, GP assessment should be part of treatment planning and risk evaluation before any dental intervention, including soft tissue manipulation.

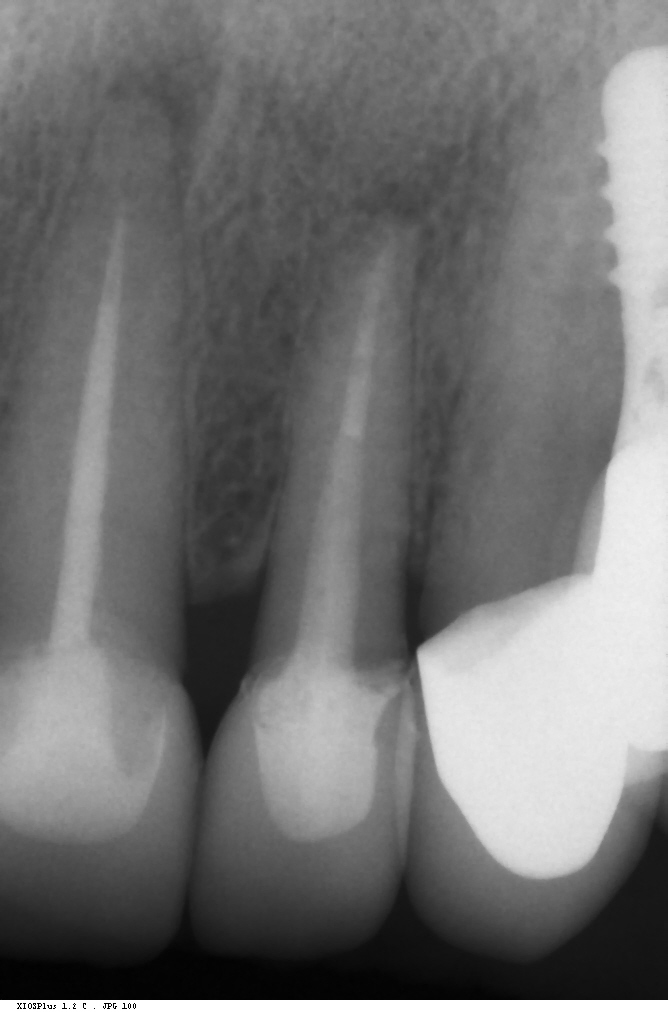

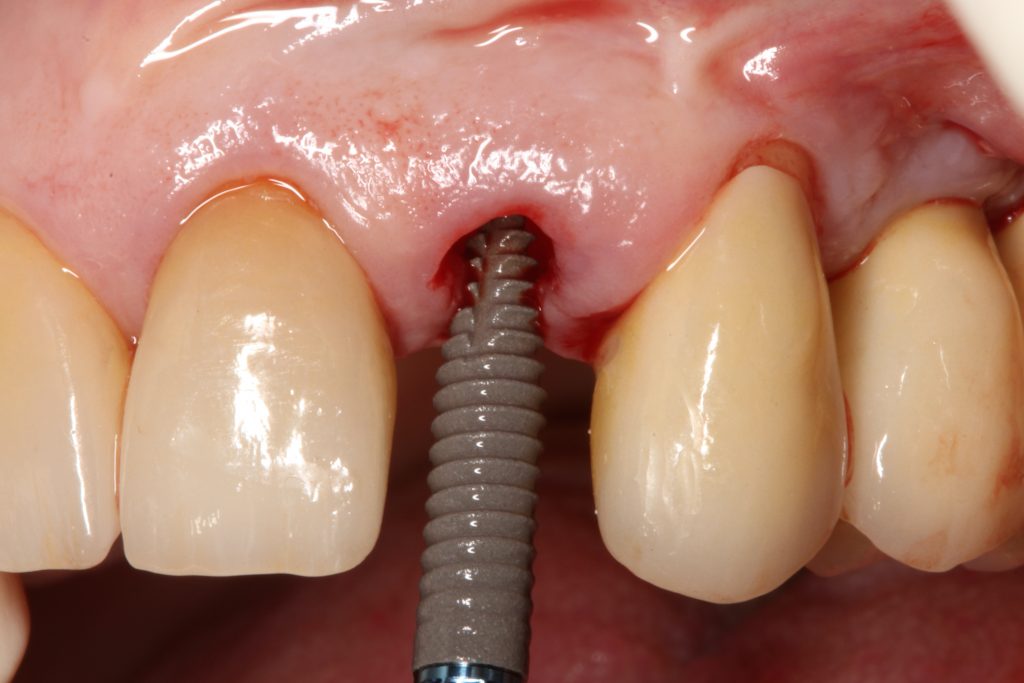

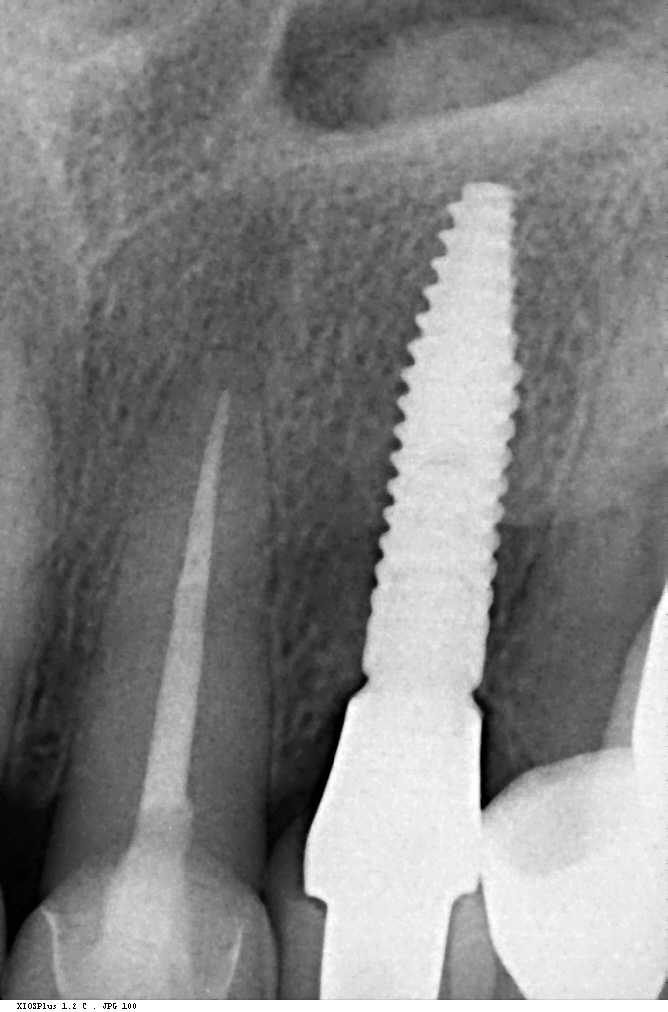

Visual assessment without any standardized method cannot be recommended and is hardly possible even for experienced clinicians (Eghbali et al., 2009). Many different methods have been described in literature like transgingival probing, ultrasonic devices, gingival transparency (TRAN) or cone beam computed tomography (CBCT). TRAN is non-invasive and the only method that does not measure GT, but directly correlates the transparency of a periodontal probe tip through the gingival sulcus with GP. If the tip of the instrument shines through, it is categorized as a thin GP; if it does not shine through, it is a thick GP (Kan et al, 2003). In line with the ITI SAC classification, a double-ended periodontal probe is introduced to allow for a more sophisticated differentiation into thin, moderate and thick GP (Fischer et al, 2018).

Traditionally, it was believed that thin GP was associated with slender or triangular teeth with high papillae, short contact points, high soft and hard tissue scalloping as well as narrow GW, while the opposite was reported for thick GP cases ( Esfahrood et al. 2013). When stratifying subjects according to their GP, our group could not find any statistically significant differences in supra-crestal gingival height SCGH – embodying bone scalloping – or CS measurements. GW, on the other hand, was found to be correlated to GP with a wider zone of attached gingiva for thick GP. Papilla height, however, seems to have no or only a weak connection with GP. Buccal bone thickness, nevertheless, seems to be correlated with a higher GT, hence, a thicker buccal bone plate might be expected in thick GP cases (Cook et al, 2011). Moreover, the difference between thin and thick GP, with regard to GT and buccal bone thickness, seems to be around 0.2 mm (Frost et al., 2015). In earlier studies, GP assessment was not based on GT measurements but rather on crown shape (Olsson & Lindhe, 1991; Olsson & Lindhe, 1993). These studies clearly showed a correlation between CS, GW, probing depths and gingival scalloping, however, no difference in GT was found. Furthermore, GT might primarily depend on tooth type and GW (Eger et al., 1996). The influence of tooth position and angulations still needs to be evaluated and only little information has been reported on differences between posterior and anterior teeth.

Clinical relevance

Besides a large number of studies trying to characterize the GP, interventional trials have investigated its influence on different treatment outcomes. Furthermore, the harmony between the so-called white and pink esthetics plays an increasingly important role and should be monitored throughout therapy (Ronay et al., 2011). Flap thickness has been found to be a decisive factor, especially in plastic periodontal surgery, in achieving maximum root coverage (Baldi et al., 1999; Hwang & Wang, 2006 ).

A thick GP, consequently, might contribute to more favorable results, even without the need for soft tissue grafting (Rasperini et al, 2020). However, applying a connective tissue graft (CTG) might help to overcome this drawback in thin GP cases (Kahn et al., 2016). Furthermore in regenerative therapy of infrabony defects, patients with a thin-scalloped gingival biotype have an increased risk for advanced midfacial recession after therapy (Cosyn et al, 2012). Recently, Chow et al. (Chow et al., 2010) reported on the appearance of gingival papillae in relation to crown shape and gingival thickness. They found that gingival thickness was positively correlated with interproximal tissue height and hence with the appearance of the papillae.

GP has a major impact on treatment protocols and outcomes in implant dentistry. GP should be assessed for risk, especially in the anterior zone (Dawson et al., 2019). Mid-buccal recession is a common risk after immediate implant placement, and studies impose proper patient selection in relation to thick GP (Chen & Buser, 2014). In a systematic review, Cosyn et al. (Cosyn et al., 2014) concluded that a thick GP, among other risk indicators (e.g., immediate provisional crown, flapless surgery, intact facial socket wall), may contribute to minimizing the frequency of advanced recession following immediate implant treatment. In addition, restorative materials may be chosen according to the GB, hence a thicker peri-implant tissue may “camouflage” titanium or gold-alloy abutments (Sailer et al., 2007; Jung et al., 2007). Furthermore, thick peri-implant soft tissues seem to contribute to more stable bone levels (Linkevicius et al., 2009; Linkevicius et al, 2010). The peri-implant phenotype (PIP) was not defined until, very recently, Avila-Ortiz et al. (Avila-Ortiz et al., 2020) presented a standard definition including thresholds for mucosal thickness, width of keratinized mucosa and peri-implant bone thickness.

Discussion

The most relevant reason for assessing GP is to identify high risk patients for soft tissue complications like the development of gingival/mucosal recession. A GP differentiation into thin, moderate and thick has been introduced in case risk assessment (simple, advanced, complex) for implant treatment in the esthetic zone (Dawson et al., 2009). In this context, a standardized tool for GP assessment is warranted from a clinical as well as a scientific perspective. This aspect together with the idea of developing a tool to differentiate between thin, moderate and thick GP led to the introduction of a double-ended periodontal probe (DBS12) based on TRAN (5). This tool was designed based on GT thresholds reported in the above study identifying extreme GP cases. TRAN methodology was introduced using a colored, plastic periodontal probe before tooth extraction. GT was measured after removing an upper anterior tooth and the GT threshold was artificially set to 1.0 mm to differentiate between thin and thick GP (4). The assessment showed 100% congruence between visual estimation and direct measurement for thin GP < 0.6 mm and thick GP > 1.0 mm.

Lately, it has been recommended to use traditional periodontal probes to assess GP in a standardized and replicable fashion with a GT threshold within the sulcus of 1.0 mm (2). Today, however, there is no exclusive standard periodontal probe when it comes to tip thickness, subdivision (1.0-mm steps vs. 3.0-mm steps) or tip color scheme (yellow vs. silver vs. black). These clinically measured values were approved in our recent pre-clinical model that also assessed applicability based on testing ratings by assessors with different levels of experience (Fischer et al., 2021). In this study, we used a traditional periodontal probe and two GP-specific methods (including DBS12). While seeing a much lower threshold of 0.5 mm compared to the often proposed 1.0 mm for a dichotomous TRAN approach using the traditional periodontal probe, threshold levels of 0.5 mm for thin vs. moderate and 0.8 mm for moderate vs. thick GP were seen for the other methodologies. A consensus between the assessors of > 90% was found for the DBS12 probe. Another clinical study assessing different methods to directly measure GT and GP found similar results with a 95% confidence interval < 1.0 mm even for very thick GP cases (Kloukos et al., 2018). Taking all these findings together, a threshold level of < 1.0 mm for thin GP and > 1.0 mm for thick GP seems questionable, at least when GT is measured within the gingival sulcus. Notably, a limitation of clinical studies is the very specific group of participants regarding ethnicity, age and inclusion criteria (e.g. periodontally healthy, non-restored teeth). Future research should include larger groups of varying age and different ethnicities to evaluate also the influence of gingival pigmentation. So far, hardly any interventional studies have been performed, hence, translation of the above findings into clinics are pending. In summary, GP shows a clear correlation with GT, GW and buccal bone thickness. GP assessment should be part of the daily clinical routine to identify in particular high-risk cases with a low GT. Utilization of a standardized approach including GP-specific tools is recommended.

Conclusion

The traditional dichotomous classification into thin vs. thick GP might not be sufficient to identify high and low risk cases for dental treatment procedures in the esthetic area; differentiation into thin, moderate and thick GP as part of the ITI SAC Assessment Tool applying a standardized and reproducible method is advocated. GP assessment based on transparency using a GP-specific tool inserted into the gingival sulcus seems to be an easy-to-perform, low-cost, non-invasive and highly sensitive approach – particularly for thin GP.