Over the past two decades, patient-centered care (PCC) has gained increasing attention. It emphasizes respect for patient autonomy, understanding their emotions and expectations, and fostering shared decision-making in treatment planning (Kogan et al., 2016). While PCC is widely accepted across healthcare fields, it still lacks a universal definition, leading to inconsistencies in its implementation (Grover et al., 2022).

Traditionally, healthcare followed a paternalistic model, where clinicians made decisions on behalf of patients. The shift toward PCC ensures that patient preferences and concerns are actively considered (McCance et al., 2011). In a paternalistic approach, when faced with a heavily decayed tooth, a clinician might lean toward extraction as the most predictable option, sometimes without fully exploring alternatives. But a patient-centered discussion can reveal the patient’s strong preference for saving the tooth, even knowing the risks and accepting a potential need for future extraction. PCC acknowledges that patients are more than just their clinical needs, it values their right to information and autonomy (Stewart, 2001). In 1969, Edith Balint described this philosophy as “understanding the patient as a unique human being” (Balint, 1969).

In the first part of this discussion on patient-centered dental implant treatment, Fakheran explored the importance of listening as a fundamental step in building trust and understanding (Fakheran, 2023). While listening may seem straightforward, true active listening requires genuine interest and intent (King, 2022). Barriers in dentistry include time-constrained appointments, use of technical jargon, and a clinical culture that often prioritizes procedural efficiency over dialogue. It is not uncommon for patients to attend their treatment visit only to later say that they had had a different expectation of the appointment and did not understand the discussions during the consultation. This highlights the importance of tailoring appointments to the patient’s needs, using clear communication and ensuring that the treatment options are explained without jargon. Tools such as pictures and videos can be invaluable in enhancing understanding, and sometimes it’s helpful to send patients home with written or recorded information to help them recall and reflect on the discussion. Patients who feel heard and understood experience reduced anxiety and improved health outcomes (Ulin et al., 2015).

Despite its importance, PCC is not consistently integrated into healthcare education. A significant barrier is the lack of structured communication and empathy training (Grover et al., 2022; Santana et al., 2018). Many healthcare professionals excel in diagnosing and treating diseases, yet formal education often overlooks patient communication and emotional intelligence (EI). EI refers to “the capacity for recognizing our own feelings and those of others” (Goleman (1996). While PCC has been explored in medicine and nursing, its application in dentistry has received less attention. Clinical excellence in dentistry has traditionally been defined by technical proficiency and diagnostic accuracy. However, as our understanding of patient-centered values evolves, it is increasingly clear that technical skills alone do not foster trust or improve patient satisfaction. Considering PCC is not just about improving communication; it’s about critically evaluating treatment options. Rather than defaulting to standardized protocols, we must ensure that our recommendations align with patients’ psychosocial status and individual needs.

EI plays a key role in bridging this gap. It shapes how clinicians navigate patient interactions, interpret concerns, and respond effectively. When a patient is diagnosed with a failing implant, a clinician who acknowledges the emotional impact and listens attentively is more likely to respond effectively than one who focuses solely on the next clinical steps. Goleman (1996) describes EI as comprising self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills, all of which contribute to patient-centered communication. While some aspects of EI may come more naturally to certain individuals, it is ultimately a skill that can be cultivated through reflection and training. Developing self-awareness, in particular, allows clinicians to recognize their own biases, emotional responses, and communication patterns, helping them adapt their approach to better meet patient needs.

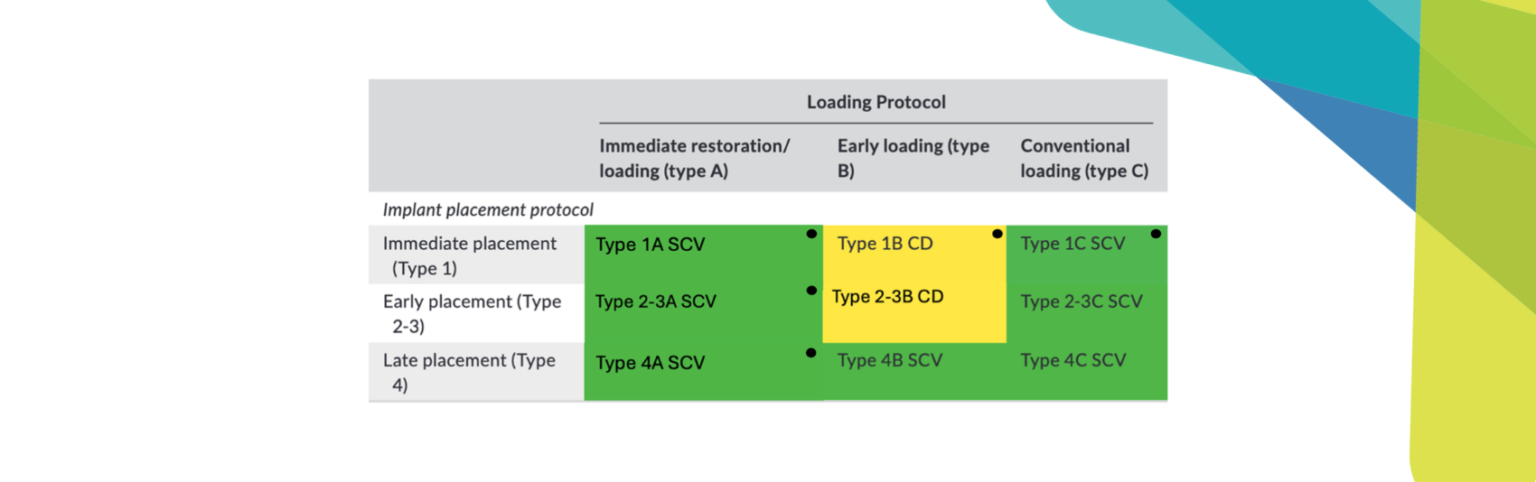

This is particularly relevant in implant dentistry, where patients often arrive with preconceived notions shaped by online information. For example, many patients expect pain-free surgery or perfect esthetics; addressing these misconceptions early with empathy helps align expectations with clinical realities. Also, misleading commercials advocating “teeth in a day” procedures can create unrealistic expectations in terms of speed and outcomes. The initial consultation plays a crucial role in building trust. Clinicians must balance providing information with giving patients space to process and express concerns, while also setting and managing expectations. Beyond building rapport, this approach lays the groundwork for PCC by ensuring treatment decisions align with the patient’s priorities rather than being dictated solely by textbook solutions.

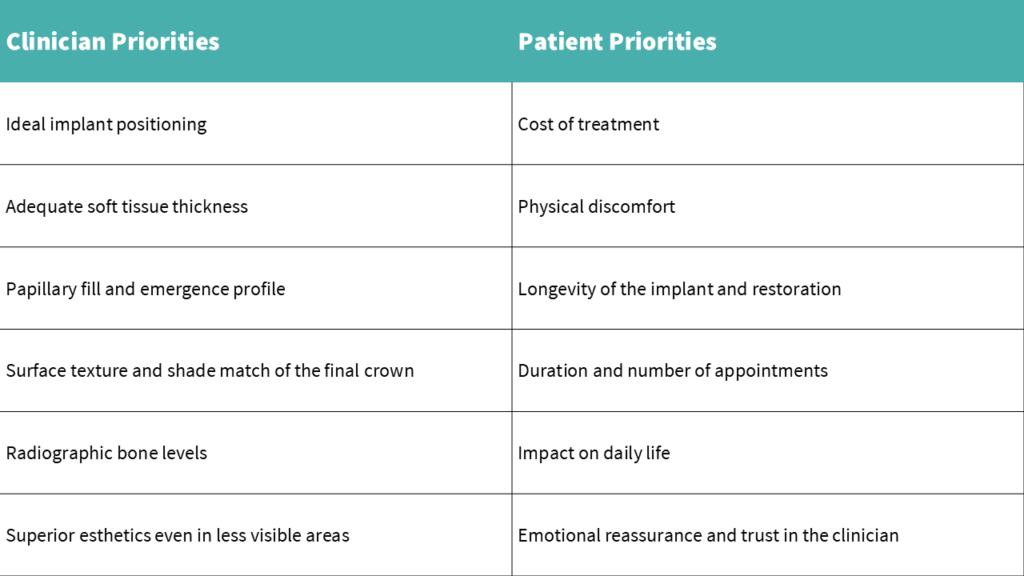

While there have been efforts to establish person-centered dentistry, implant dentistry still lacks enough research in this area (Böhme Kristensen et al., 2023). The number of studies assessing patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in implant dentistry is increasing, but gaps still exist in terms of appropriate tools and clear terminology. Most of the tools that are used to assess PROMs are created for clinicians rather than patients such as the pink and white esthetic scores. Even the term “satisfaction” is broad and subjective, varying from patient to patient. Thoma (2022) notes, “The best treatment is not necessarily the one that shows the highest efficacy, but the one that suits the patient’s preferences.” Patients most often inquire about longevity, pain, and cost rather than the millimetric clinical measurements prioritized by clinicians (Thoma, 2022). Identifying what matters most to the patient allows for more tailored and effective treatment.

A crucial question for clinicians and researchers in implantology is whether we are overtreating patients. Every treatment decision should weigh the pros and cons, including morbidity, clinical outcomes, and patient values. For example, soft tissue augmentation, such as connective tissue grafting, is the standard of care in the esthetic zone to improve mucosal thickness (Jung et al., 2022). However, it may not always align with patient priorities. Some patients seek implant therapy primarily to avoid removable prosthetics and may not prioritize soft tissue esthetics. Performing an additional surgical procedure that increases discomfort and donor site morbidity without a perceived benefit to the patient may contradict the principles of PCC. It can be challenging for clinicians to know how much information to provide, especially when a patient initially expresses a preference for the simplest or least expensive option. However, ethically, patients should still be informed of all appropriate treatment options, given time to reflect, and once their preferences are clearly understood, care should be tailored to align with their individual values.

Studies illustrate how patients and clinicians may prioritize different aspects of treatment. For instance, Waller et al. (2020) found that patients often have a higher acceptance threshold for gingival color discrepancies than clinicians, suggesting that what clinicians perceive as critical may not always matter to patients, particularly when weighed against additional cost and morbidity. However, in other cases, patients may fixate on esthetic details that clinicians consider minor, such as slight asymmetry or minor gum recession, which can significantly impact patient confidence and satisfaction (Abrahamsson et al., 2017). These contrasting perspectives reinforce the importance of open communication to ensure both functional success and meeting patient-centered esthetic expectations.

A clinician’s intrinsic motivation to provide excellent care extends beyond technical proficiency. Recognizing that implant dentistry is not just about placing implants but about building relationships encourages a more holistic, patient-centered approach. While research into patient priorities is growing, no dataset can fully capture what truly matters to every individual. Human experiences are too nuanced to categorize, which is why acknowledging each patient’s autonomy, values, and unique context must come first.

Digital technologies are increasingly enabling more patient-centered outcomes in implant dentistry. Software platforms such as Smilecloud and coDiagnostiX empower clinicians to engage patients in the treatment process by providing visual, interactive representations of proposed outcomes. For instance, Smilecloud allows clinicians to create facially driven smile designs that patients can visualize and co-approve before any irreversible procedures take place. Similarly, coDiagnostiX enables precise virtual implant planning and guided surgery, helping clinicians explain surgical steps clearly and reduce patient anxiety through greater transparency. These digital tools enhance communication by making abstract treatment goals tangible, allowing patients to better understand, question, and personalize their care. Intraoral scanners, CBCT imaging, and CAD/CAM systems also streamline workflows, often reducing the number of appointments, an important priority for many patients. When applied with empathy and intent, these technologies not only improve clinical precision but also reinforce the collaborative and individualized nature of patient-centered implant dentistry.

A truly patient-centered approach begins with this understanding and translates into clinical behaviors that reflect it. This includes taking time to understand what matters most to the individual in front of us, asking open-ended questions during consultations, and being willing to adapt our recommendations based on the patient’s circumstances and values. Structured training in communication and empathy can help clinicians develop these skills, while regular reflection on personal biases encourages more balanced and respectful treatment planning. Moving toward patient-centered implant care is not about abandoning clinical standards, it’s about ensuring those standards are applied in a way that genuinely aligns with the people we serve.