Introduction

The therapeutic approach to treating the fully edentulous maxilla is in continuous evolution due to the advances in technology that have dramatically expanded the possibilities for esthetic optimization in the field of dentistry.

The rising esthetic demand as well as the digital and technological improvement in the dental industry over recent decades have created a paradigm shift in full-arch restorative treatment.

Each patient is unique and will have different demands and expectations. As clinicians, we have to identify patient needs to avoid over-treatment and propose the most appropriate approach according to their clinical situation.

It is important to reassess our idea of the therapy we wish to offer the patient by subjecting them to an esthetic “checklist” at each major stage of the treatment, such as acquiring a full patient medical and dental history (their needs and expectations), surgical records, and a full clinical examination.

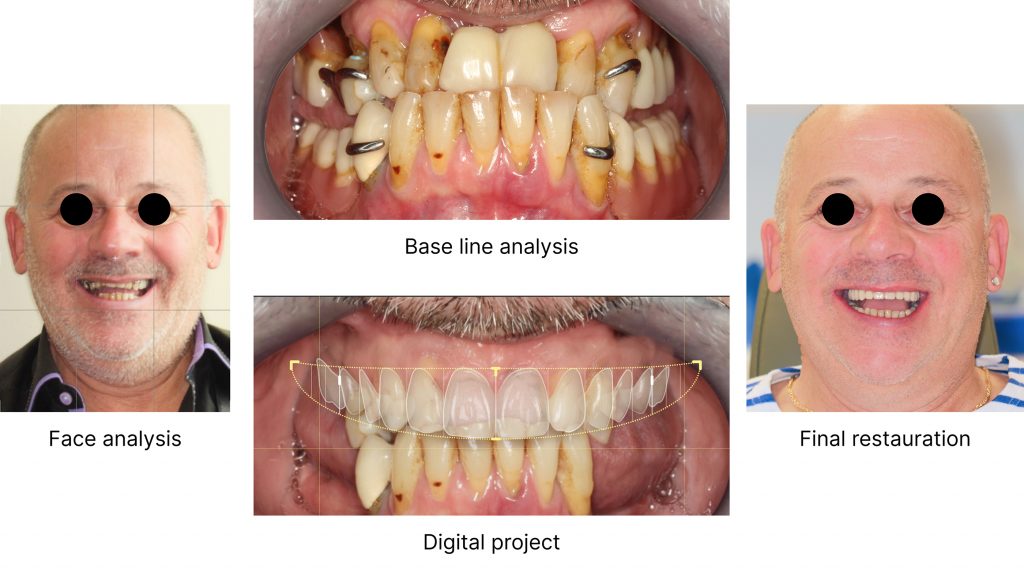

This article will describe the protocol used in our practice for the treatment of full arch cases. Each step should be carefully taken into consideration, including extra- and intraoral esthetic analysis of the patient, with photographs, digital pre-visualization using any system that offers smile design simulation, and a mock-up for clinical pre-visualization using a transparent guide for dentate patients and a wax rim replica for edentulous patients.

Each of these steps will be illustrated using my clinical cases.

Data acquisition – documentation series at the initial appointment

The usage of dental photography has evolved throughout the years, from being a quintessential teaching mechanism to one of the primary tools that allow us to record accurately the clinical situation of our patient at the baseline to measure and ensure we achieve the best outcome at the end of the treatment.

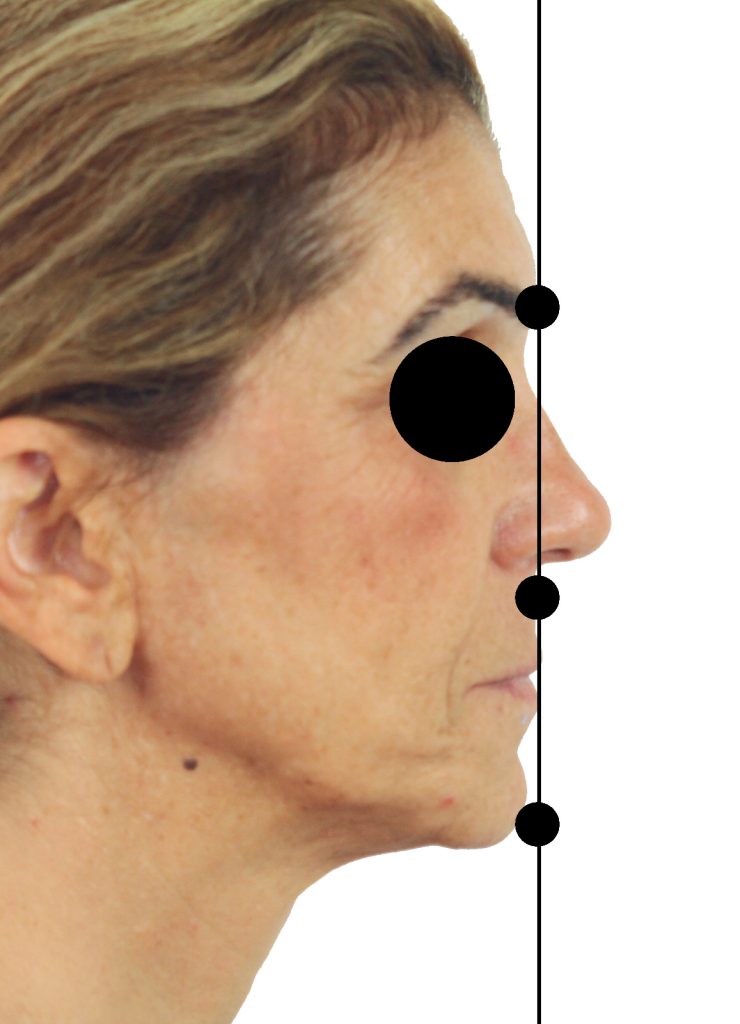

Extraoral photos

The extraoral facial profiles are essential to understanding the patient’s current situation. Thus these photos will allow the clinicians to assess whether the patient is orthognathic, prognathic, or whether there is a diminished nasolabial angle. We ao collect photos from multiple views (frontal, lateral, and lateral views at 45 degrees) to analyze the facial thirds, midline, symmetry, and smile line (Fig. 1). All these photographs are gathered during the initial appointment to provide the necessary knowledge with which to establish and compile the most optimal treatment plan.

Video acquisition

Video acquisition is also important as it provides a visual in a dynamic form. This includes analyzing the patient’s personality, facial expression, lip movement, and smile type. These are critical elements in moderate-to-complex oral rehabilitation as they are imperative in determining harmonious facial support and the transition line. Without them, an incorrect diagnosis can lead to disharmony, especially for patients with a high smile line who will require an Fp-3 prosthesis (Misch Classification Fixed Prosthetic – composite defect, replaces missing crowns and gingiva), this transition line, from an esthetic point of view, if visible, can have a negative impact on our prosthetic outcome (Fig. 2).

Macro/mini/micro-esthetic concept

Seeing the big picture in modern dentistry requires evaluating the patient as a whole, and not just focusing on the alignment of the teeth (Sarver 2020). The overall appearance of the patient is the first and most important consideration, and this is followed by the smaller elements of the smile and then the esthetics of the teeth.

The approach described in this blog comes from a set of terms related to the macro-esthetics of smile design from an orthodontic perspective described by Prof. Sarver (Sarver 2020). This blog further expands the descriptive process to include a broader approach to esthetic treatment, dividing prosthetic evaluation into three categories.

Macro–esthetic

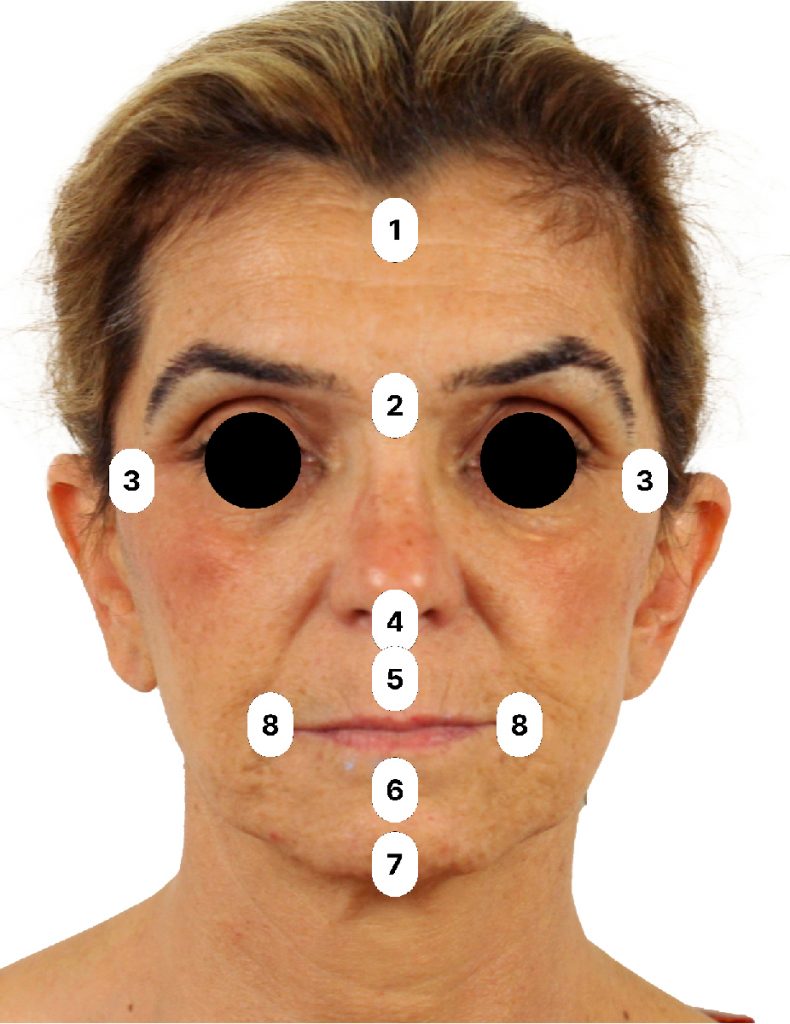

The key to this fundamental approach is the systematic analysis of all anatomically static and functionally dynamic facial and smiling components. This leads to a greater appreciation of the subtle interactions of each of the facial elements and how each can be appropriately managed through a unified treatment approach.

Esthetics should not be viewed as the sum of a series of characteristics nor should they make up the entire diagnosis but are rather a critical component. Esthetics can be subjective, however, utilizing a model analysis can help to identify the common parameters for an esthetically pleasing appearance. Faces are judged to be beautiful or appealing if the pattern of the features pleases the observer. Macro-esthetics are exactly what you see when you step back and examine the patient’s face for symmetry and proportion. The details of macro-esthetics are shown in the image below (Fig. 3).

- Trichion

- Glabella

- Zygomatic width

- Base of nose

- Upper lip vermilion

- Mentolabial sulcus

- Inferior symphysis

- Buccal commissure

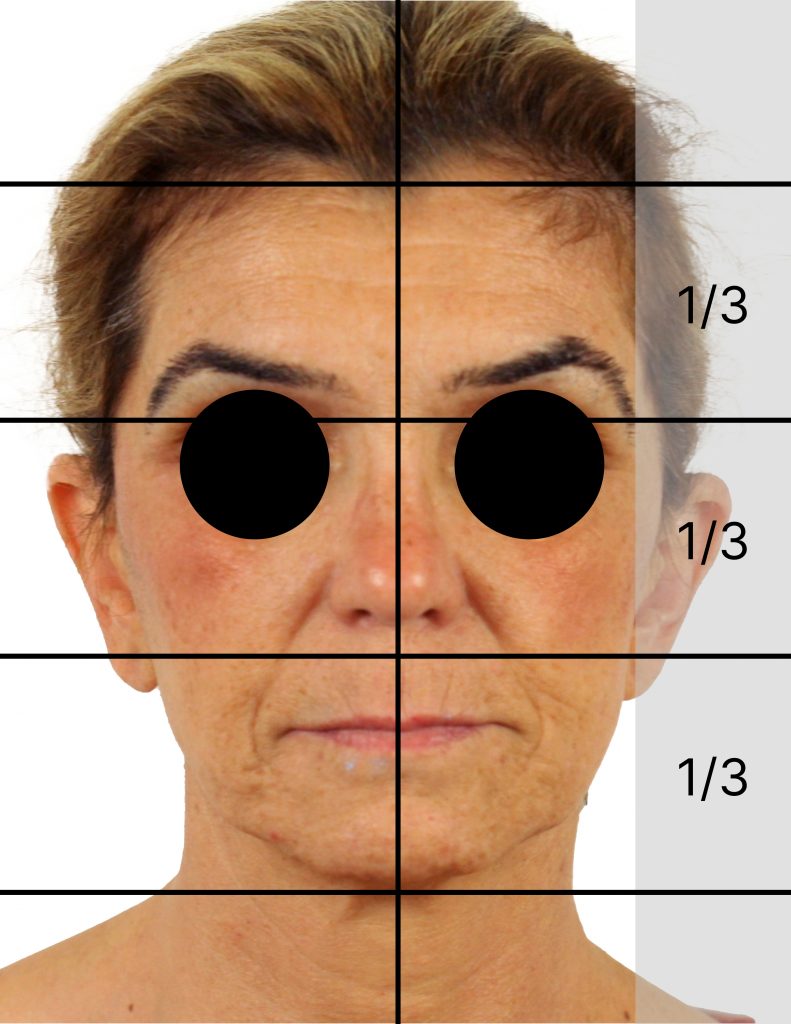

One of the most important aspects of the overall proportions of the face is facial symmetry. An assessment of facial symmetry begins by establishing the mid-sagittal plane (Fig. 4). The inter-pupillary plane and smile lines (the connection of the outer commissures) should be perpendicular to the mid-sagittal plane and parallel to each other.

The classic description of the symmetric esthetic face says that there are equal vertical thirds, with the upper third of the face measured from the trichion (the lowest part of the hairline) to the glabella (Fig. 6).

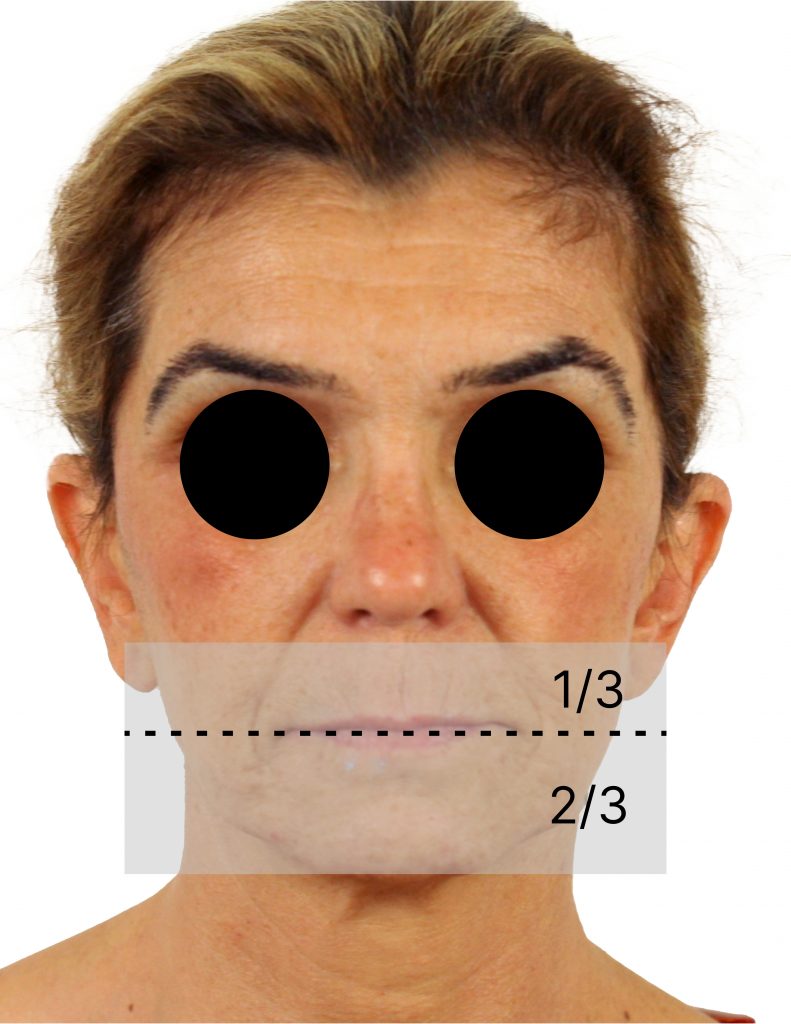

The middle third extends from the glabella to the nasal cavity, and the lower thirds of the face encompass the distance between the base of the nose and the gnathion (Fig. 5). The lower third can again be subdivided into thirds, consisting of one-third for the upper lip and two-thirds for the lower lip and chin. It is important to recognize the contribution made by the chin which is often overlooked. To assess the vertical proportions of the face, the ideal lower third of the face is made up of one-third of the upper lip and two-thirds of the lower lip and chin.

We should use these anatomical landmarks as treatment references, however, as clinicians, we often focus on the disproportion in the lower third. It gives us information about possible skeletal deformities or asymmetries that can direct the clinician in the treatment approach and determine if interdisciplinary treatment is needed to achieve a more ideal proportion of the lower facial thirds.

Often clinicians tend to focus on the dental area and fail to consider the overall facial esthetic analysis to treat our patients as a whole, with their symmetries and asymmetries.

It is essential to obtain excellent interdisciplinary collaboration, especially with the clinician responsible for the prosthetic part. The final prosthetic restorations must fully integrate the particularities of the facial setting to meet functional and esthetic requirements.

Facial view

The starting point described by Sarver for the macro-esthetic examination is the frontal view. The classic frontal analysis categorizes faces as mesocephalic, brachycephalic or dolichocephalic. The analysis between these facial types has to do with the proportionality of facial width and facial height: Dolichocephalic faces are longer and narrower in comparison to the brachycephalic faces which are broader and shorter.

This analysis from the frontal view provides a starting point for a multidisciplinary treatment approach. Altering the macro-facial structure can either be done more invasively with maxillofacial surgery, or less invasively with orthodontic treatment to achieve a more balanced face type.

The frontal view provides extensive information for analysis, however, when evaluating the skeletal information, the lateral view provides crucial information on the maxillo-mandibular relationship.

Straight profile – orthognathic

The second analysis in the macro-esthetic analysis is from a profile perspective. The vertical facial thirds should also be applied in a profile view. As mentioned earlier in this blog article, the landmarks used are the glabella, the base of the nose, and the chin (Pogonion). If the line drawn vertically is straight through the anthropometric points, these patients are classified as having an ideal skeletal relationship. The visual axis is what would determine the natural position of the head. This axis does not always approximate the Frankfort horizontal plane.

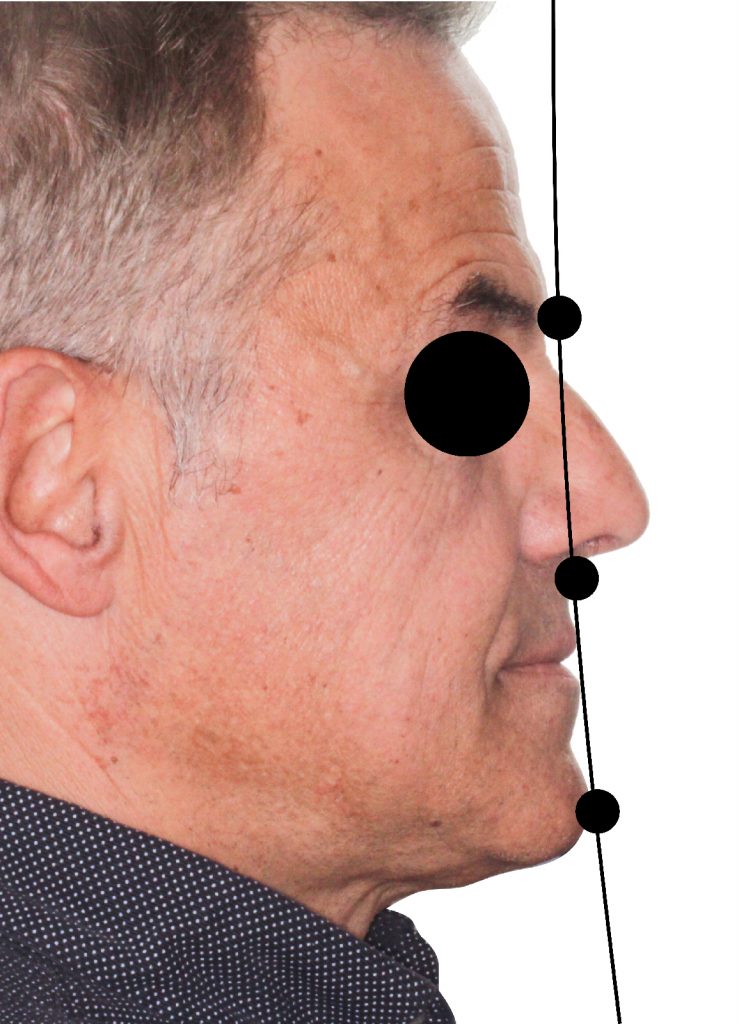

Based on the position of the mandible and of the maxilla relative to this point, a patient’s profile will be described as “straight”, “concave”, or “convex”. The patient’s head should be in a natural position when evaluating this profile. This is important for an accurate evaluation of the profile. Fig. 7 illustrates the anterior facial plane formed by lines connecting the glabella to the base of the nose (subnasale) and the chin point (pogonion). Different research groups have defined various soft tissue parameters and landmarks of soft tissue facial analysis. Legan and Burstone (1980) described the angle of convexity which is formed by soft tissue glabella, subnasale, and soft tissue pogonion. The normal range described by Burstone for a straight profile is between 165-175 degrees. Less than 165 degrees gives a convex profile, and more than 175 results in a concave profile. The profile is important, it informs us about the anteroposterior part of the maxillomandibular relationship when considering the possibilities for orthognathic surgery (Fig. 7).

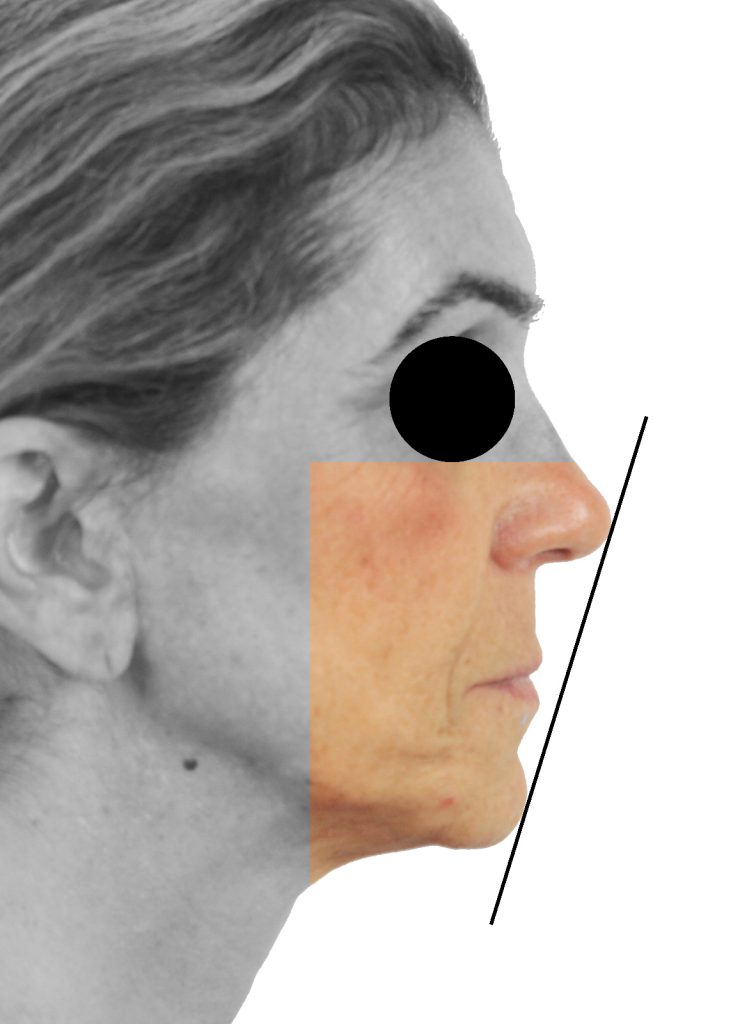

As seen in Fig. 8, the patient has a slight convex profile, also known as prognathic, whereas in Fig. 9, the patient has a concave profile or a so-called retrognathic skeletal relationship. The profile analysis is important because it gives us information on the anteroposterior position of the maxilla and mandible.

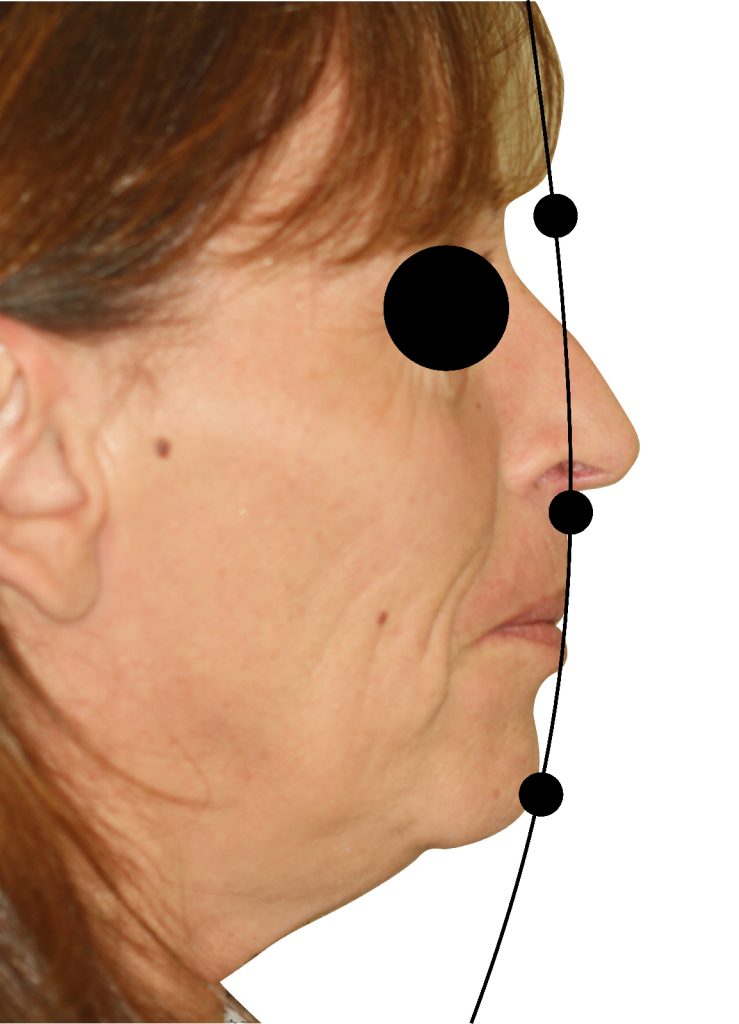

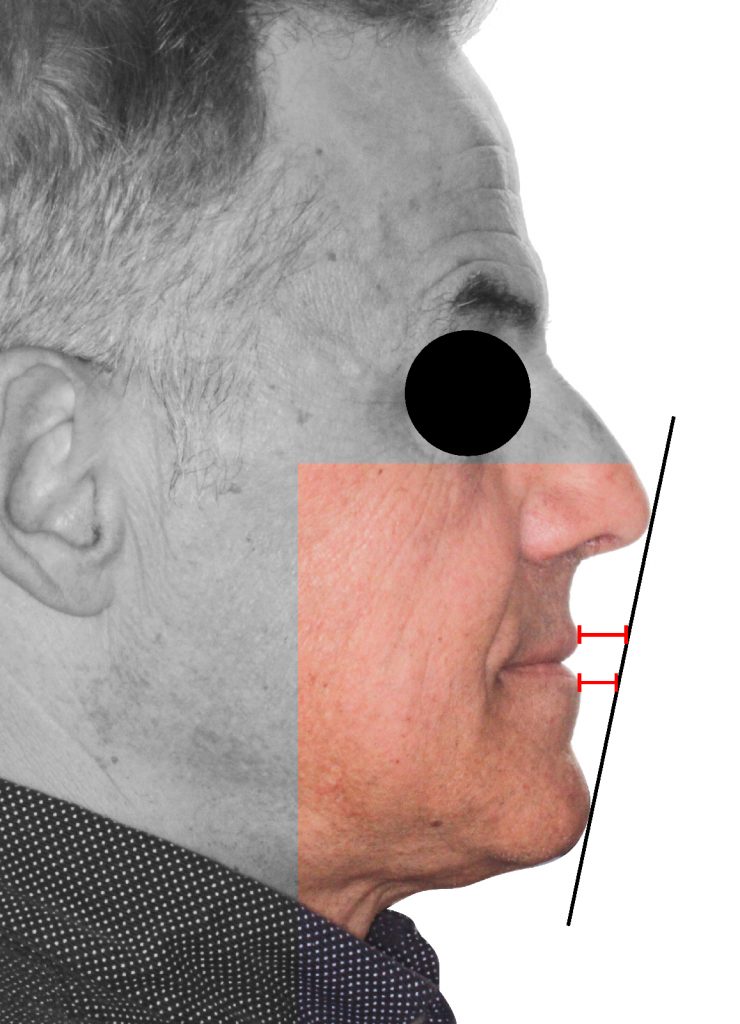

Facial harmony – Rickets – esthetic E-line/plane

When analyzing harmony in the lateral aspect, the clinician could also look into the esthetic line/plane (E-line/plane), first coined by Rickets in 1954 who used this assessment by taking an arbitrary line from the tip of the nose to the chin. The goal of this evaluation is to ensure harmony between the nose, the lips, and the chin.

The lower lip should be about 2 mm behind the esthetic plane, and the upper lip should be 4 mm behind in the average Caucasian face (Fig. 10). However, this average may differ according to ethnicity. This E-line/plane helps to create greater harmony between these three anatomical facial structures.

Ricketts stressed the importance of the balance of the lips, relative to the nose and the chin. This suggests that excessively protruded or retruded lips in relation to the average were unharmonious and unesthetic. If we look at the patient in Fig. 11, his upper and lower lips are too far behind, which creates a visual imbalance, and the nose and chin dominate the lower thirds. Therefore, using the E-line/plane to assess the lateral profile can provide us with information on how to create a balanced facial harmony.

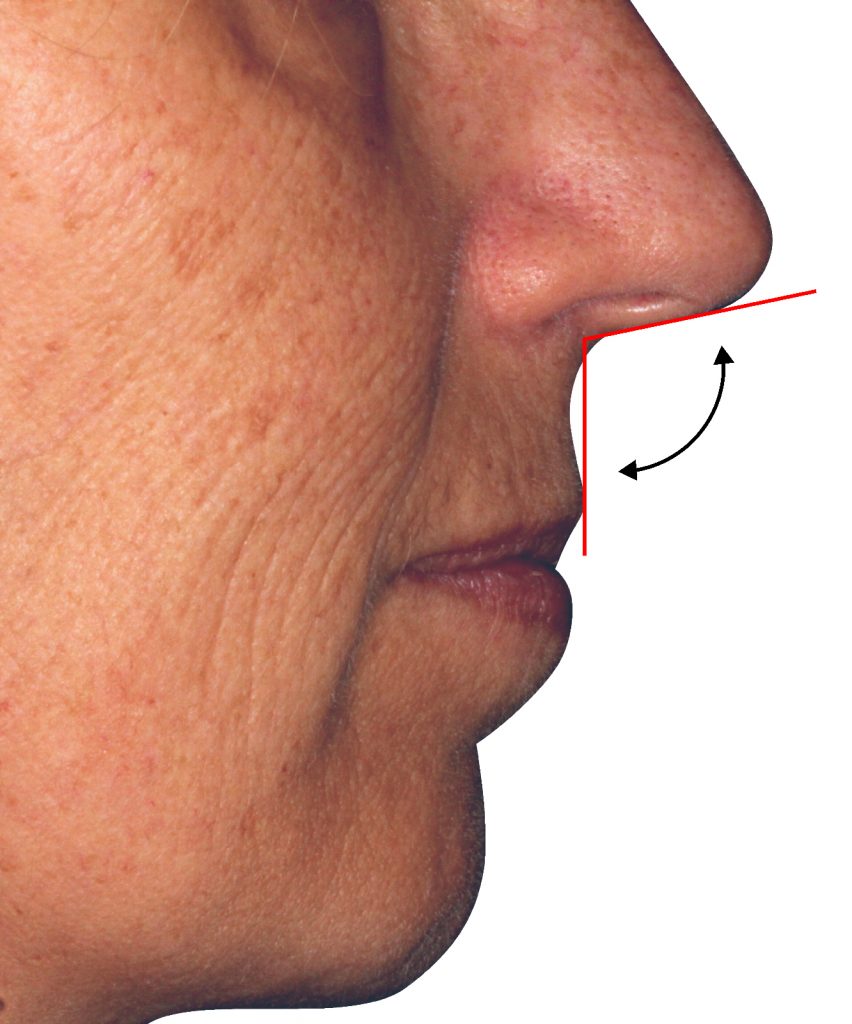

Upper lip support – nasolabial angle

The nasolabial angle is the angle formed by a line tangential to the upper lip and a line tangential to the columella. This can range from 90° to 120° (Fig. 12). The nasolabial angle is determined by several factors such as the anteroposterior position of the maxilla, the anteroposterior position of the maxillary incisors, and the vertical position or rotation of the nasal tip. This can result in a more obtuse or acute nasolabial angle, and the soft tissue thickness of the maxillary lip also contributes to the nasolabial angle. A thin upper lip favors a flatter angle, while a thicker upper lip favors an acute angle. This analysis is a common parameter that is considered when planning the treatment for full-arch maxillary rehabilitation.

Edentulous patients may have insufficient upper lip support. We have to acknowledge this and understand the patterns of resorption of the maxilla and the mandible. Depending on the chronology of a patient’s history, whether older or younger, the severity of resorption may lead to a decreased vertical dimension and a deeper nasolabial angle. As part of the treatment, the clinician’s role is to rebuild the missing hard and soft tissue to restore the nasolabial angle (Peck & Peck 1995).

Transition line

The transition line as described by Bedrossian (2008) is an imaginary line that marks the border between the residual periodontium and the most apical part of the future prosthesis. In those cases where a prosthesis with artificial gingiva needs to be made, it is imperative that this line is not visible at the end of the prosthetic treatment.

A high proportion of our patients present a medium or high smile line where the papillae are visible. According to Tjan & Miller (1984), eight to ten teeth are visible in 90% of smiles and twelve teeth in only 4% of cases. Regardless of the age group, the determination of the transition line between the natural gingiva and the artificial teeth or gingiva becomes essential. An incorrect assessment of the transition line will have consequences that cannot be corrected once the implants are placed.

Bone resorption can also lead to esthetic consequences, therefore it must be carefully analyzed and discussed with the patient before any treatment. This could be a factor that will influence the choice of the treatment plan, the type of surgery, and the type of prosthesis for the final outcome following the clinician’s suggestions, the patient’s wishes, and the patient’s needs.

The evaluation of the smile, as done in the past with a photograph, often shows a static image of a forced smile that does not reflect the reality of a spontaneous dynamic smile in everyday life. The use of videography offers a significant advantage. This was described by Van Der Geld et al. (2007) who showed that patients uncovered more of their teeth during spontaneous smiling with videography.

The correct incisor position

The teeth are the backbone of the smile, and the position of the maxillary incisors plays a fundamental role in influencing phonetics, lip support, and function. This must be carefully evaluated to ensure an esthetic outcome (Bidra 2010; Bidra 2011; Sarver 2001).

The position of the incisal edge is specific to each individual and should not be moved to satisfy esthetic requirements. It is essential that the esthetic attributes coincide and are related in particular by phonetic and functional attributes (Fig. 13).

The “F” and “S” are the sounds affected by the position of the incisors and are the easiest to analyze. The “F” sound is dependent on the placement of the incisal edges of the maxillary central incisors in relation to the lower lip, without involving the mandibular incisors. When the patient pronounces words starting with “F” like “father” or “family”, the incisal edges of the maxillary central incisors should be flush with the vermilion edge (the junction between the wet lip and dry lip) of the lower lip. As for the “S” sound, patients often face pronunciation problems (lisping). In most cases, this is due to excessive contact between the maxillary and mandibular incisors when pronouncing these phonemes, which should be suppressed (Daas et al. 2020; Calamita et al. 2019).

Ideally, all these parameters should be validated using a temporary removable prosthesis or a mock-up, especially if several parameters need to be corrected, such as the lip support and nasolabial angle (Fig. 14).

This provisional can later serve as a radiographic template and as a surgical guide. The temporary removable prosthesis can be used once the implants have been placed, if for any reason immediate loading is not the right indication.

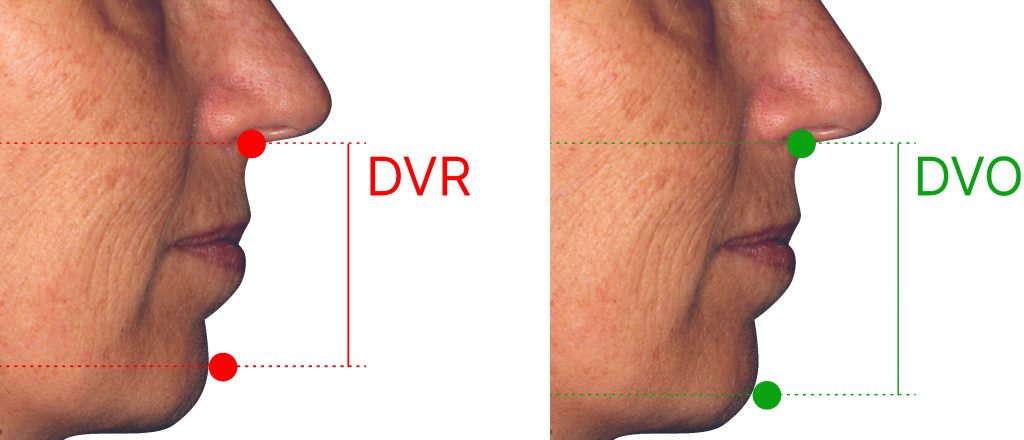

Vertical dimension of occlusion (VDO)

The esthetic and functional success of implant-supported full-arch restorations for single-arch reconstruction or fully edentulous patients is strongly dependent on several parameters, and one important parameter is the vertical dimension of occlusion (VDO). Defining and registering a comfortable, esthetic, and functional VDO for an implant-supported restoration is extremely important to help determine the amount of available prosthetic space for moderate to complex reconstructions when involving a single arch or more.

There are many different techniques when it comes to evaluating the VDO. One of the more common ways is the interocclusal rest space (freeway space) to determine the difference between VDR (Vertical dimension at rest) and VDO (Vertical dimension at occlusion). The average freeway space (VDR – VDO) is approximately 3 mm in difference (Fig. 15). Other techniques such as following existing dentures, facial esthetics, phonetics, swallowing, craniofacial landmarks, and cephalometric evaluation can also be used.

Mini-esthetic

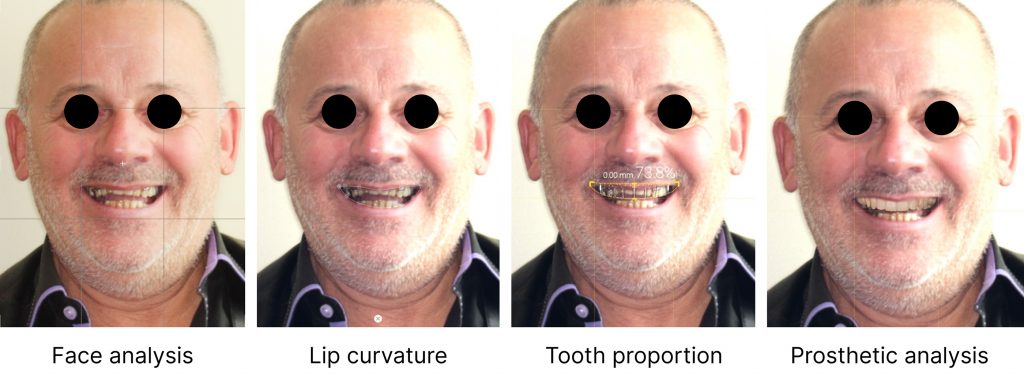

The mini-esthetic focuses on the display of the teeth and the smile – it is a detailed view and it is a good starting point for any rehabilitation (Fig. 16).

Several studies have measured the esthetic impact felt by observers according to the number of teeth visible in the jaw when smiling. According to Tjan, 8 to 10 teeth are visible in 90% of smiles and 12 teeth in only 4% of cases. Dunn points out that non-expert subjects mainly judge smiles to be more esthetically pleasing with more tooth display (Fradeani 2006; Hulsey 1970; Tjan & Miller 1984; Vig & Brundo 1978).

There are many factors that we should take into consideration. For instance, it is known that women tend to display more teeth than men, and as you get older it may be appropriate to show fewer teeth when the lips are at rest. The reason for this is that muscle tone decreases with age, and the upper lip droops. Also, in the event of a broad smile with bone deficit in the maxillary posterior regions, rehabilitation with a shortened dental arch (less than 12 teeth) should be avoided to prevent unesthetic blacked-out regions.In our practice at the initial appointment, if we have an older patient who would like to show more upper teeth, we would communicate to the patient that this may be harder to achieve unless we have a multidisciplinary approach that includes a plastic surgeon.

Smile line

The components that define the maximum esthetic potential have been extensively discussed in the literature. The smile line, also known as the “smile arc” was defined as the relationship between the curvature of the incisal edges of maxillary anterior teeth (upper incisal line) and the curvature formed by the lower lip upon smiling.

According to Dong et al., 60% of patients present a “consonant” smile type (the curvature of the upper incisal line similar to the curvature of the lower lip when smiling); 34% present a “flat” or non-consonant smile type (a flattened upper incisal line in relation to the curvature of the lower lip), and 5% are “inverted” in which the upper incisal line forms an opposite curvature to that formed by the lower lip.

We must also take into consideration the smile and how the maxillary occlusal plane relates to the lower lip. Some of our patients may present a straighter occlusal plane which is considered to be more unbalanced: the lip curvature increases towards the corners, the cuspids and the bicuspids may be cut off, which is seen as non-constant. Also, some of the more challenging patients to treat are those who present with the occlusal plane in a reversed curve (Fig. 17).

In the mid-1980s, Tjan and his collaborators established a classification of the smile according to the importance of the visibility of teeth and gum tissues (Tjan & Miller 1984). As stated in the study, the proportion of patients with a high or medium smile line represents 80% of the population that is more prone to esthetic risk. Certain reservations can be expressed as to the result of this study. In this particular study, the target population was between 20 and 30 years of age, of both sexes and all ethnicities. However, we know that this characteristic seems to vary according to the gender, ethnic origin, or the age of the patients. A high smile line was found to be more common in women.

It is important to evaluate the smile not only from the frontal aspect, but also from the lateral aspect. This comes from the approach when setting denture teeth for fully edentulous patients, where we want to make sure that the cuspids and the bicuspids increase with the lower lip curvature so we can provide a constant esthetic smile (Fig. 17).

Horizontal aspect

The horizontal aspect is also important and is regarding the buccal corridors. The buccal corridors are defined as the space between the buccal surfaces of the maxillary teeth and the corners of the mouth during a smile. Centripetal bone resorption in the maxilla creates wide buccal corridors which in the case of implant-supported prosthetics will require the creation of distal cantilevers, which will not be without consequences for the reliability of future rehabilitations.

But with the aid of the wax rim and the smile analysis during our appointments, we can communicate with the laboratory and fill out the horizontal aspect of the smile (Fig. 18).

Micro-esthetic

Tooth proportion

The final aspect of our analysis is the tooth proportions and gingival symmetry (Magne et al. 2003). In terms of perfect proportions, the golden ratio (1:1.618) has long been the benchmark in full arch rehabilitation, anterior rehabilitation, and complete/partial removable prostheses, an area where prosthetic freedom is greater.

Other authors believe, given the diversity of the population, that dental esthetics should not be restricted by dogma. Indeed, the mathematical probability of finding one of these ideal ratios in a smile is very low and only a minority of smiles comply.

However, maintaining good proportions between the width and the height of the maxillary anterior teeth as well as the proportions of the teeth between them. There are many different tooth proportion evaluation techniques, such as golden ratio, golden percentage, RED, Preston, DSD, CHU, etc.; these are tools to help establish an esthetically pleasing smile. In the event of bone resorption, these proportions can be easily maintained by resorting to false gingiva while avoiding additional surgeries.

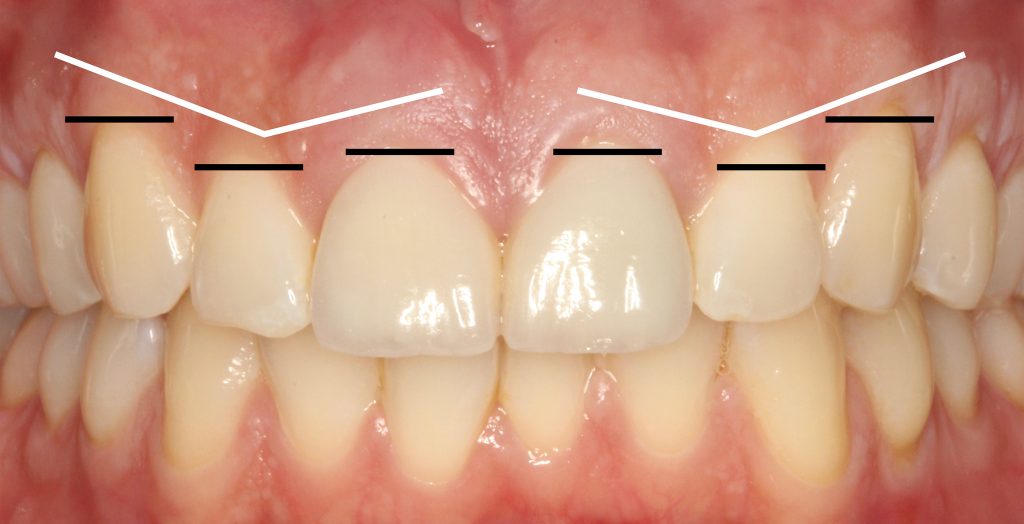

Gingival symmetry

The literature shows that most patients would prefer the gingiva of our natural dentition to be harmonious. Where the gingival margins of the central incisors are at the same level, the lateral incisors are slightly coronal to the central incisors, and, last, but not least, the gingival margins of the canines and central incisors are at the same level (Fig. 19). This provides an image of high-low-high symmetry regarding the anterior sextant (Kokich et al. 1984).

Summary of analysis

Complete implant-supported rehabilitation in the maxilla is a complex treatment. This involves a set of parameters, both functional and esthetic, which must be taken into consideration. It is necessary to follow a simple but rigorous protocol to progress step by step from the first consultation until the treatment proposal (Fig. 20). Multiple softwares could aid in accomplishing this, such as Digital Smile Design, Trios Smile Design, Smile Cloud Design®, etc. (Fig. 21).

Conclusion

The esthetic analysis must be done in close collaboration with the patient to determine the desired changes. It is necessary to devote the time needed to understand the patient’s expectations and thus assess his or her requests. However, the patient’s desires should be within good clinical practice for the clinician. The therapeutic decision will emerge by understanding the gap between what is wanted and what is possible.

The general, local, clinical, radiographic and photo/videographic examinations will allow the necessary information for the diagnosis to be collected. An esthetic assembly, using the parameters described, will then allow the prosthetic treatment plan to be validated together with the patient.

The number of teeth to replace, the choice of reconstruction type (fixed or implant-retained, with or without false gingiva), the materials used (resin, ceramic, titanium, zirconia, or other), the chronology of the treatment, and even the budget will be all elements that can only be determined once the in-depth study has been carried out. This will help guide our choice towards the type of treatment suitable for each patient.

The analysis of the elements of the face and the dynamic movements of the lips in relation to the dental, dento-labial, and phonetic parameters are one part of the many protocols necessary to obtain optimal esthetics. Nevertheless, this is a good starting point for any prosthetic rehabilitation. A checklist of parameters followed point by point of the various diagnostic elements will provide an excellent way to facilitate the overall vision of the criteria to be taken into consideration.