Background

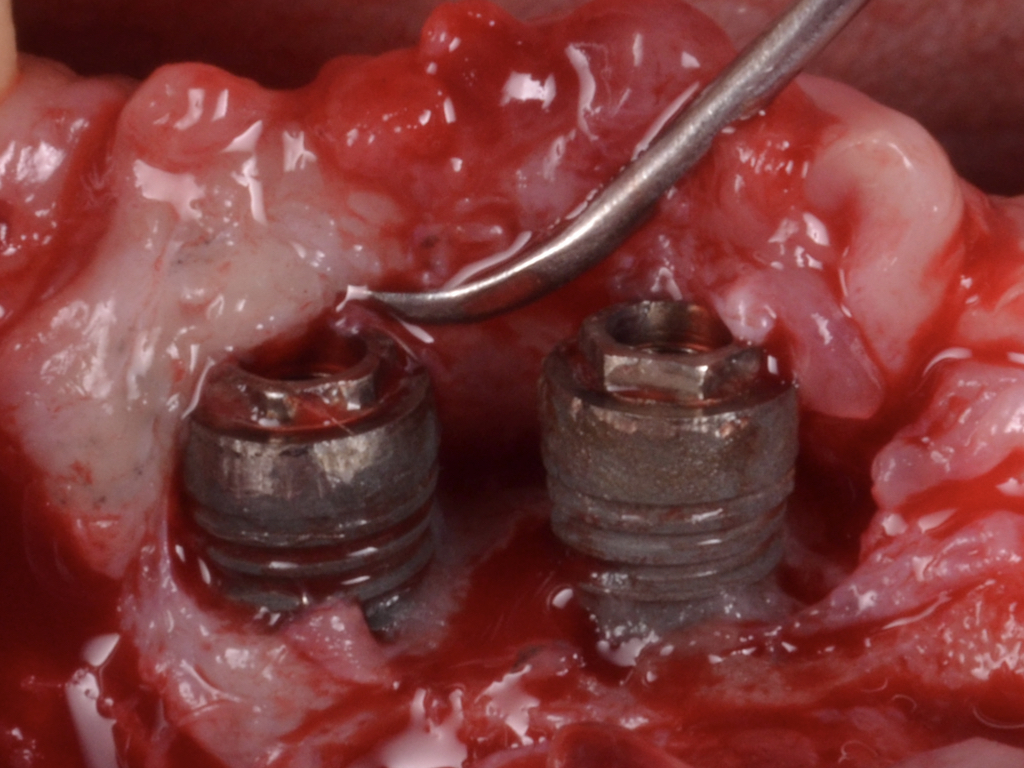

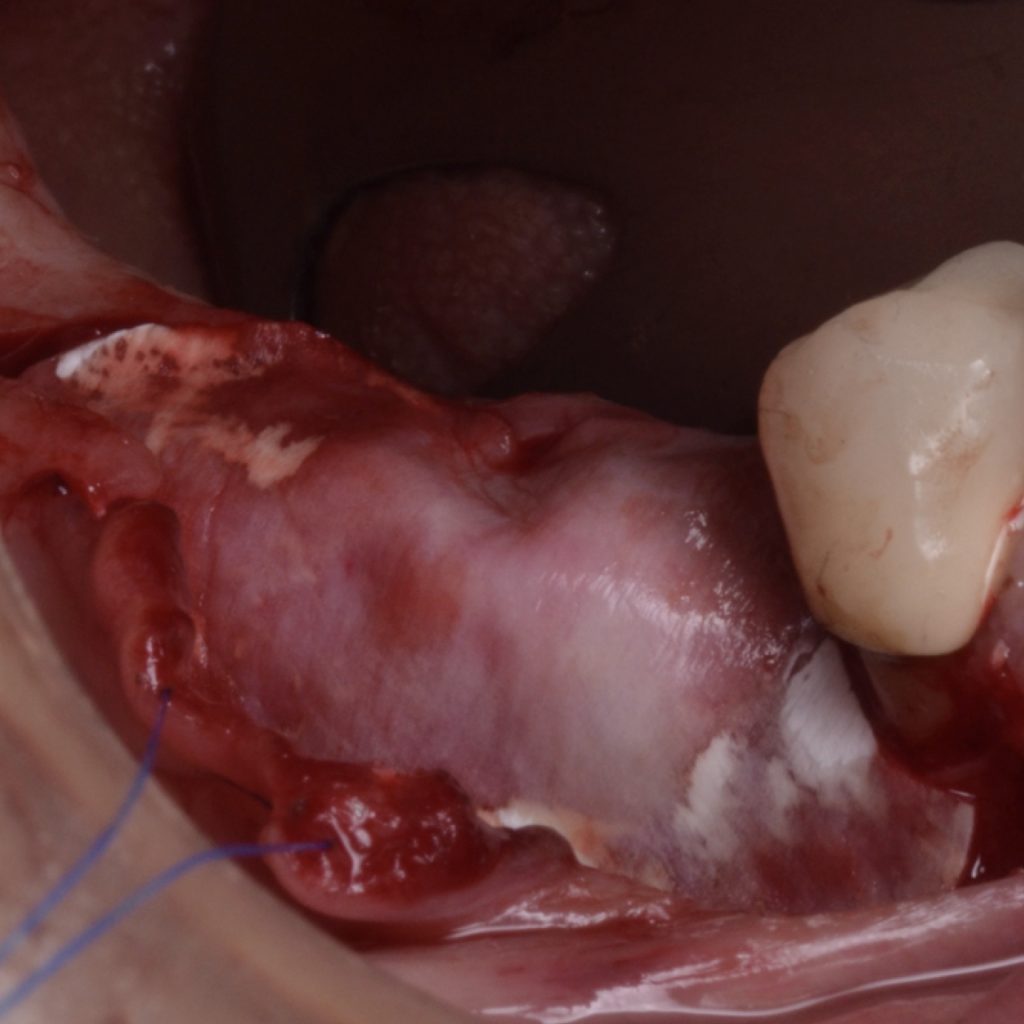

Peri-implantitis is regarded as a biofilm-mediated inflammatory condition that leads to progressive bone loss (Fig. 1). In addition, it is suggested that peri-implantitis leads to an increased systemic status of inflammation (Blanco et al. 2021; Chaushu et al. 2020). This may increase an individual’s susceptibility to life-threatening conditions (Blanco et al. 2021). Therefore, peri-implant infections must be promptly diagnosed and eliminated.

The therapeutic target in managing this disorder is to shift from an anaerobic towards an aerobic ecosystem to arrest disease progression. Accordingly, the primary endpoint must be to close the peri-implant pocket (≤5mm). To achieve such a goal, nonsurgical measures have shown unsatisfactory outcomes regarding disease resolution (Hentenaar et al. 2020). Hence, surgical strategies are often demanded to achieve stability. This therapeutic option demonstrates enhanced predictability and effectiveness levels in the long-term stability of the peri-implant hard and soft tissues (Faggion et al. 2013).

The surgical therapeutic modality relies upon multiple aspects that have to be meticulously examined. Generally, peri-implantitis-related contained bone defects are prone to favorable reconstructive/regenerative outcomes and a consistent reduction in the pocket depth (Schwarz et al. 2010; Aghazadeh et al. 2020). On the other hand, applying the principles of bone regeneration to non-contained defects is discouraged. Resective measures are advocated, including osseous recontouring and/or soft tissue resective surgery. This review aims to provide some tips and pearls for successfully managing peri-implantitis.

Technical principle behind the therapy of peri-implantitis

The goal in the surgical therapy of peri-implantitis from the technical perspective is to shift from a negative to a positive or flat bone architecture that assists in the resolution of inflammation. Hence, in supra-crestal lesions, the goal is to flatten the bone using osteoplasty/ostectomy, while in intra-bony lesions, a flat architecture is reached through bone reconstruction.

Peri-implantitis bone defect morphology

Bone defects are classified according to defect morphology and the and the number of supporting walls.

- Class I: Intrabony defect

- Class Ia: Buccal dehiscence

- Class Ib: 2/3-wall intrabony defect

- Class Ic: Circumferential intrabony defect (4-wall defect)

- Class II: Supracrestal defect

- Class III: Combined defect

- Class IIIa: Buccal dehiscence + supracrestal defect

- Class IIIb: 2-3 walls intrabony defect + supracrestal defect

- Class IIIc: Circumferential intrabony defect (4-wall defect) + supracrestal defect

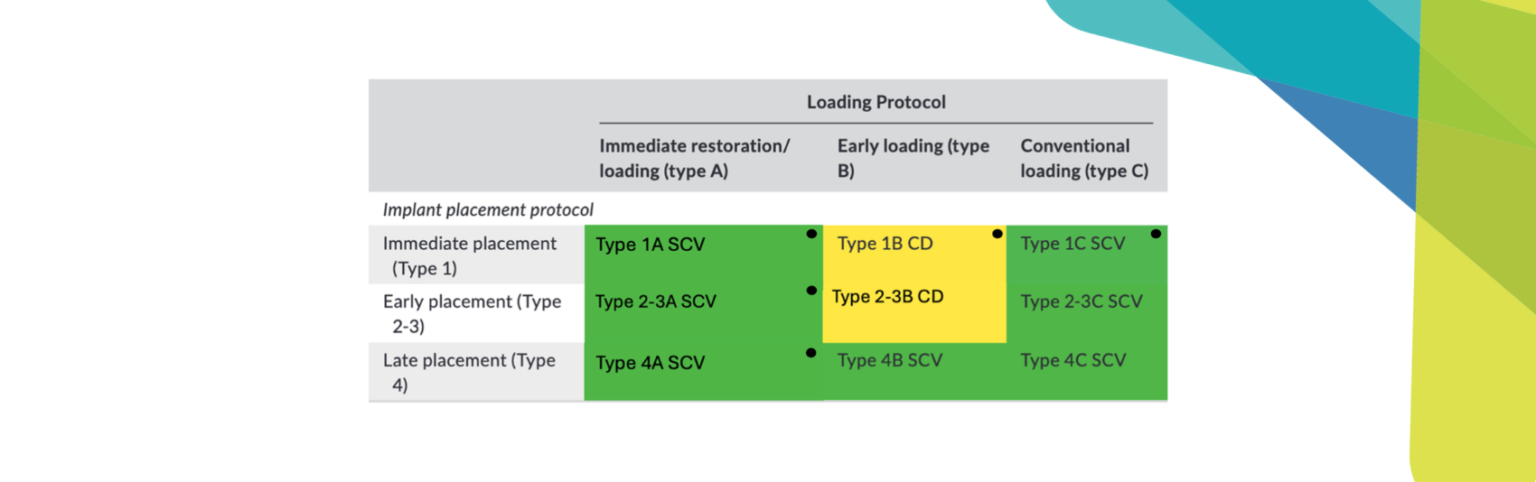

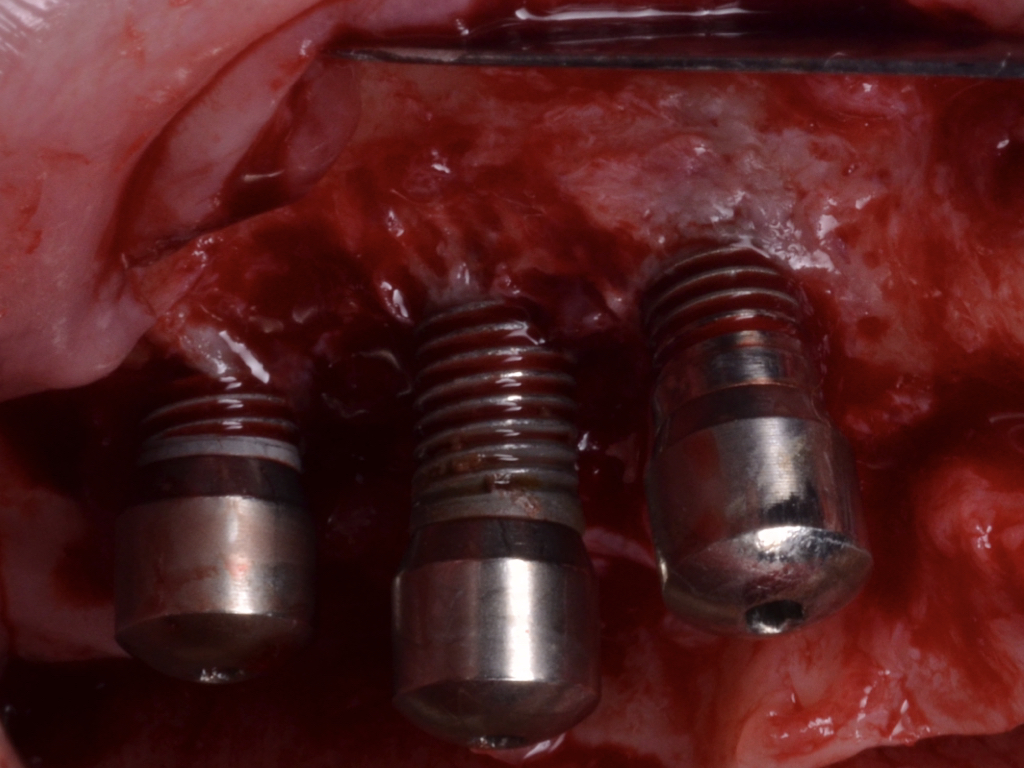

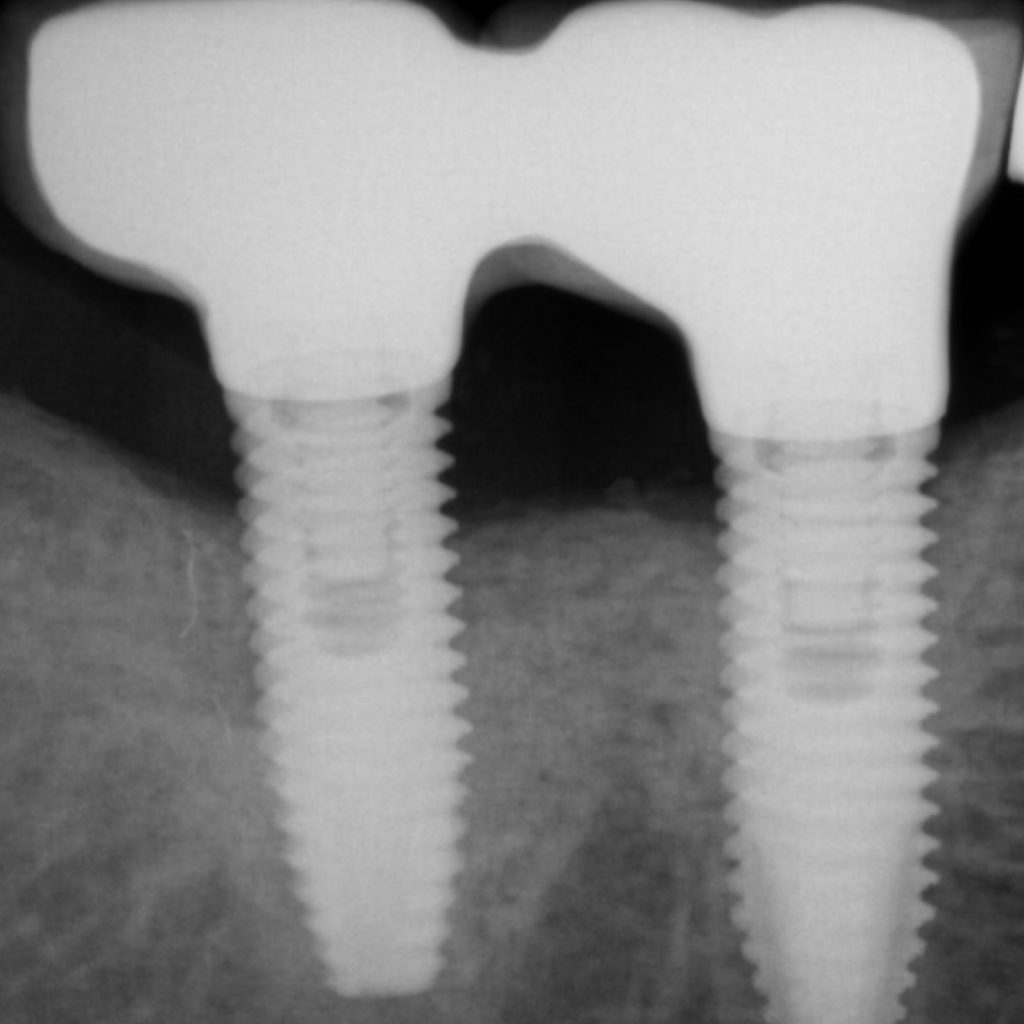

Resective therapy

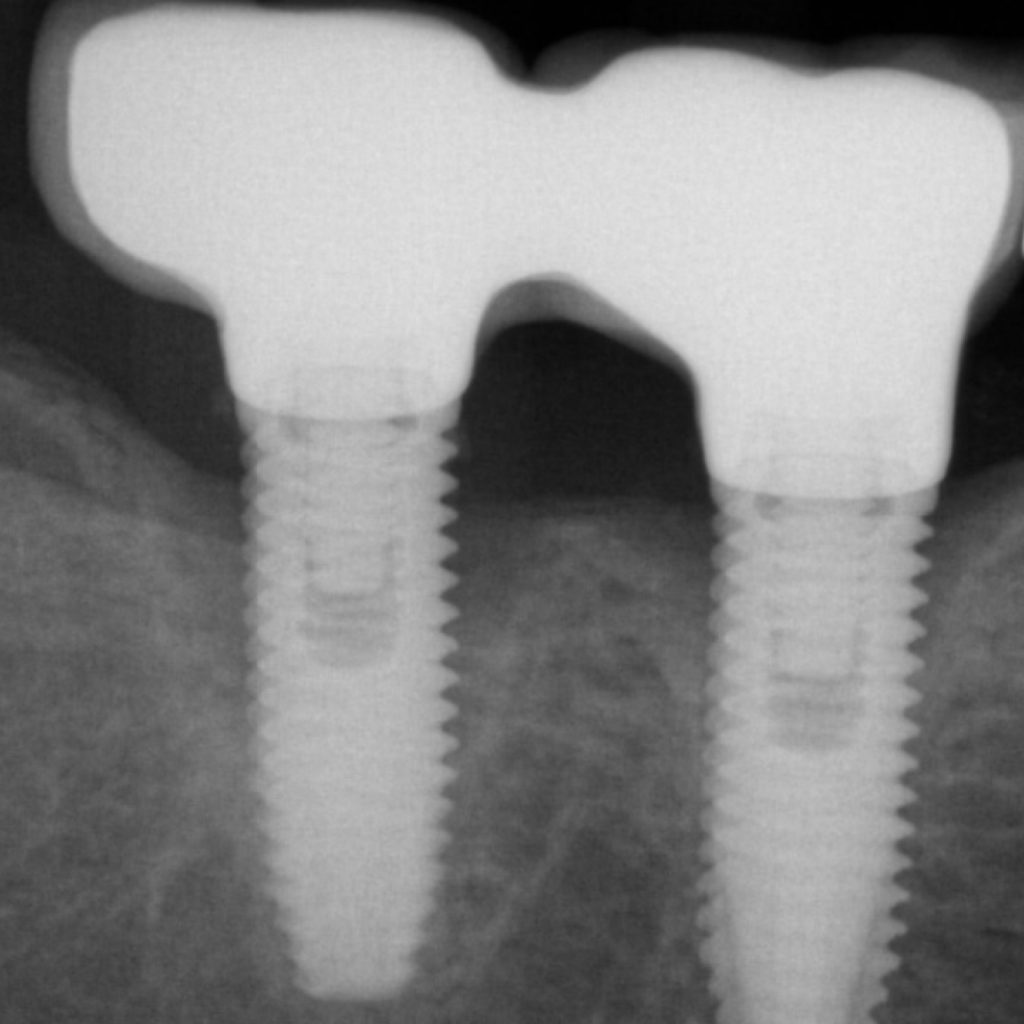

This therapeutic modality is applied to non-contained defects. Non-contained defect configurations might be attributable to the lack of adjacent bony peaks, implant position, or the pattern of bone loss in a bucco-lingual perspective. In other words, class Ia, II, and IIb are candidates for resective therapy (Fig. 2).

Flap design relies primarily on bone defect depth assessed using bone sounding and the width of keratinized mucosa (KM). It must be kept in mind that the goal is to reduce pocket depth; nevertheless, maintenance of ≥2 mm of keratinized mucosa on the buccal aspect is desirable. In scenarios with a narrow band of keratinized mucosa at the buccal aspect, a conservative approach in the buccal aspect is recommended as well as limiting excision to the palatal/lingual aspect. If no KM is present whatsoever, simultaneous soft tissue conditioning using a free epithelialized graft is indicated (Monje et al. 2020; Monje et al. 2021). For that, a full-thickness flap should be raised in the crestal area to access the uneven alveolar bone architecture and a partial thickness on the buccal flange to leave the periosteum attached to the bone. Osteoplasty and/or ostectomy must be performed with a diamond bur at the crestal aspect. Implantoplasty is recommended given that the implant surface will be deliberately exposed to the oral cavity, and any macro-geometrical (threads) and micro-structural (topographic roughed characteristics) features may lead to re-contamination of the pathogenic microbiome. The flap should be apically repositioned using an external vertical mattress suture.

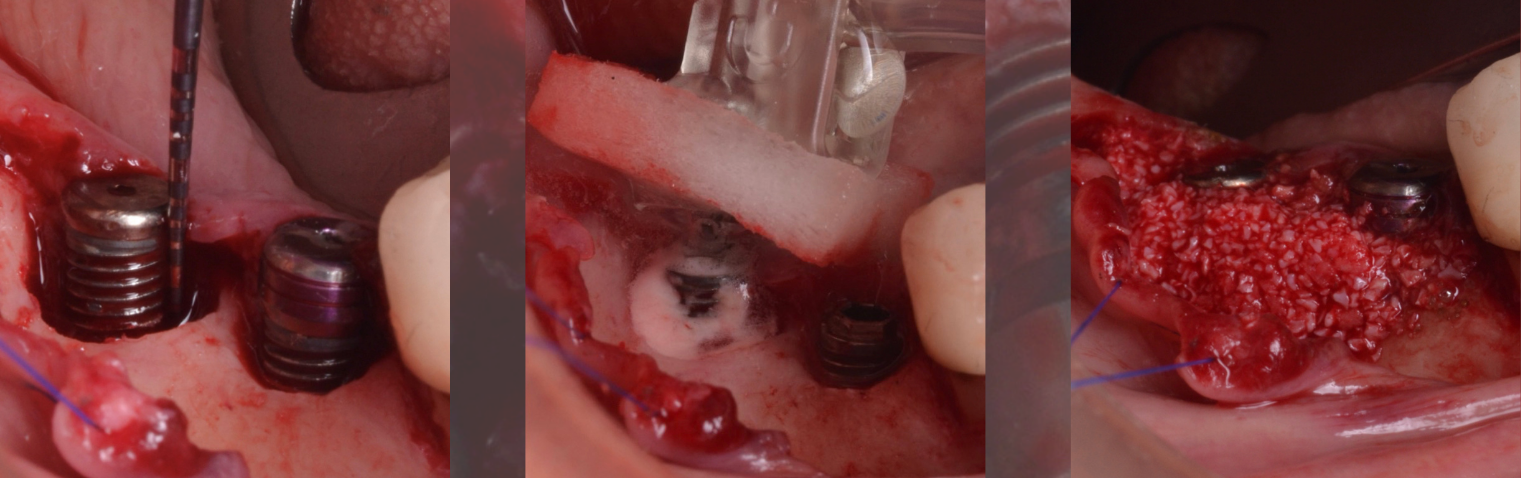

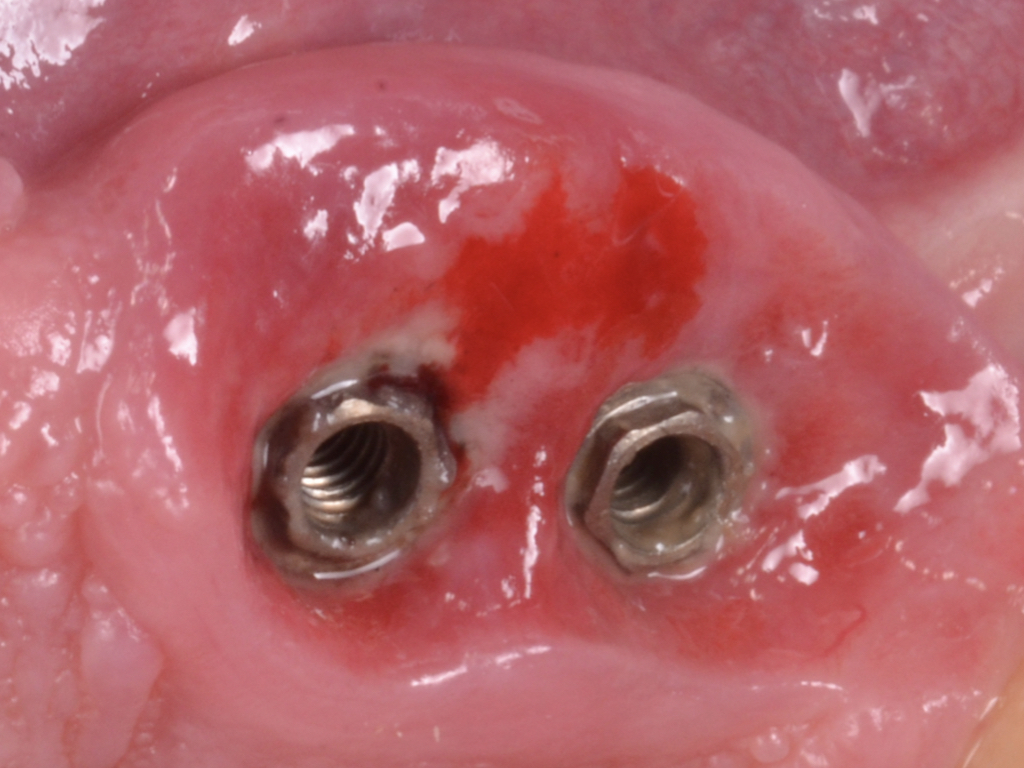

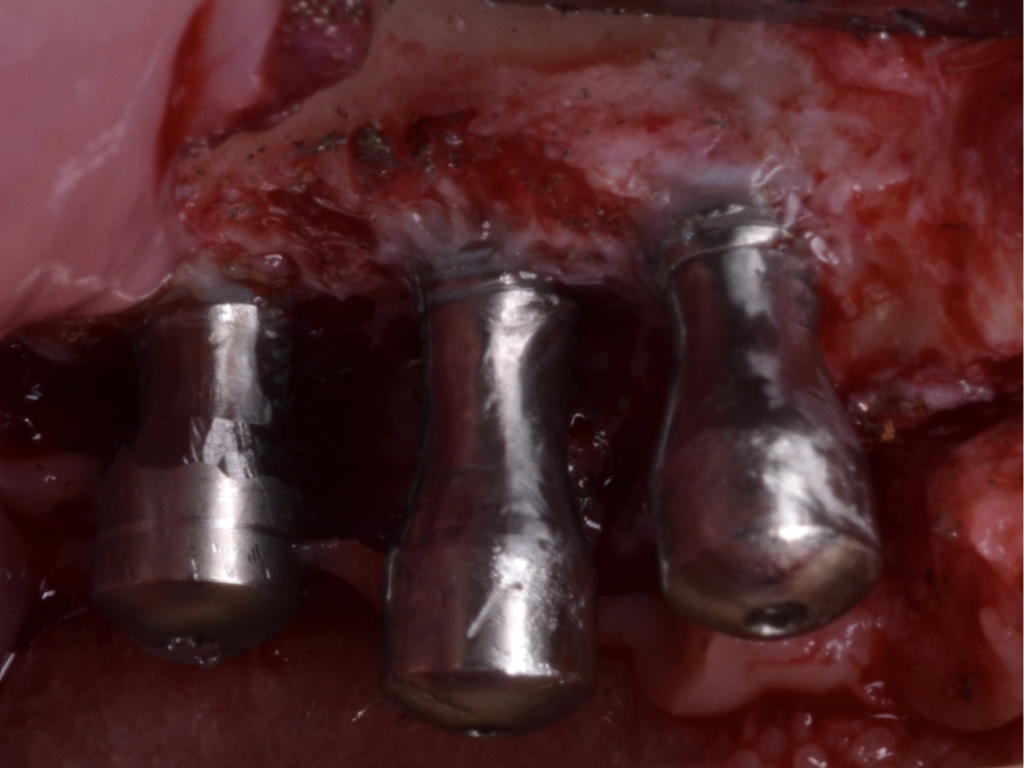

Reconstructive therapy

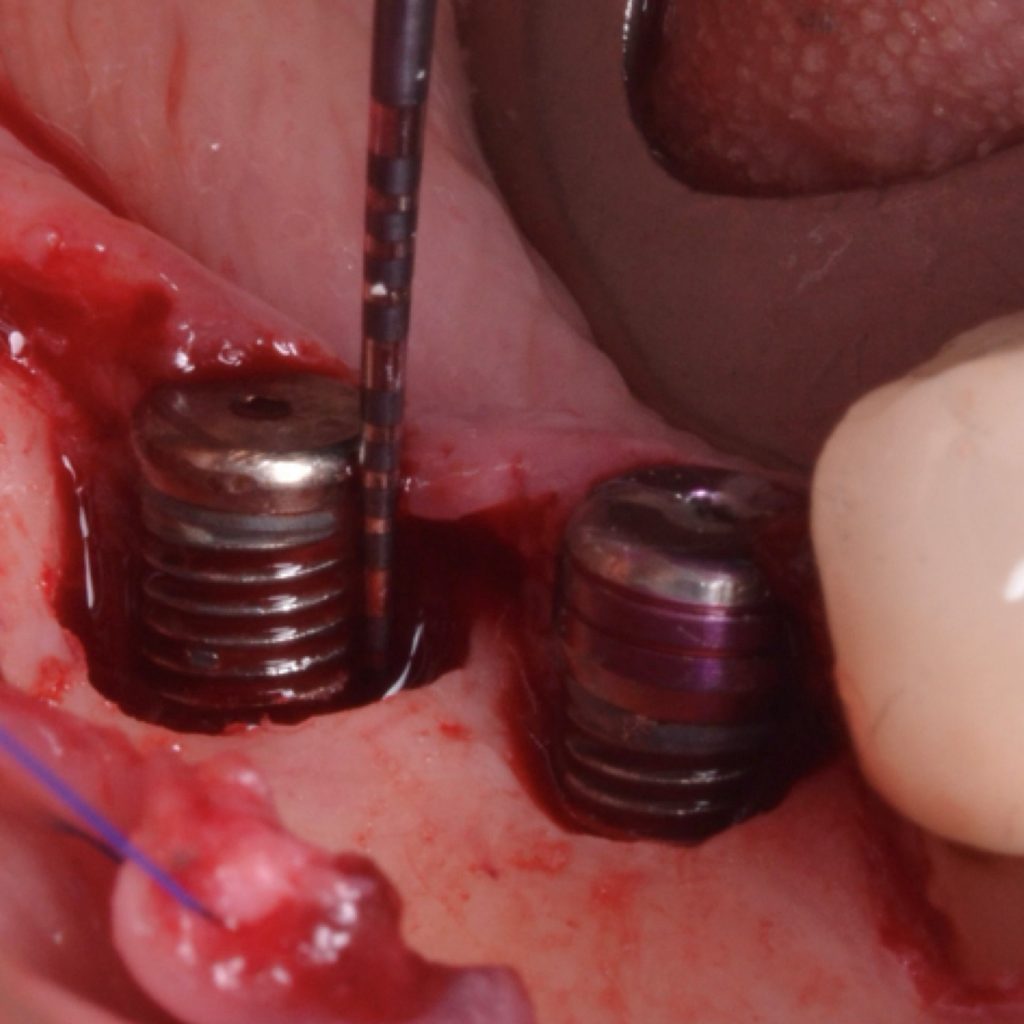

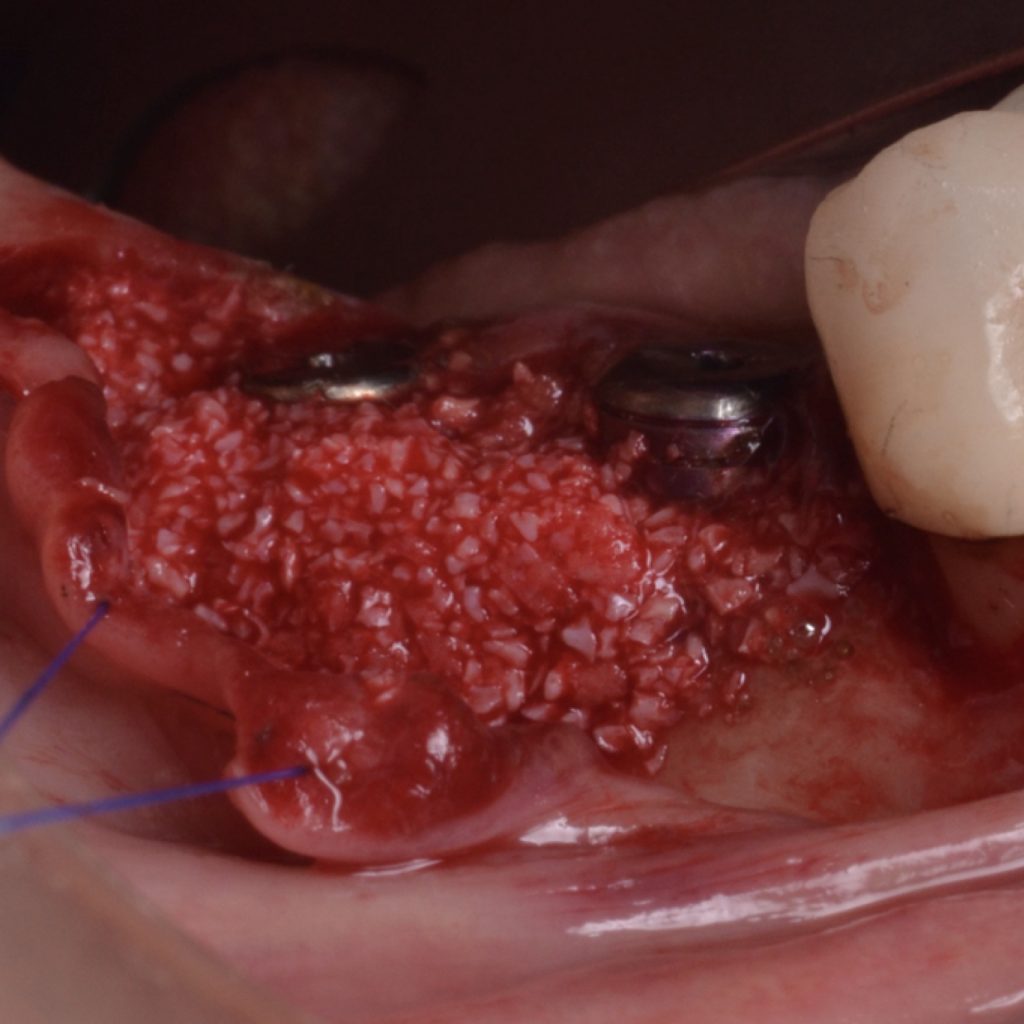

A full-thickness flap must be raised to achieve access. Subsequently, debridement can be performed with curettes or ultrasonic devices. Surface decontamination is key to success (Fig. 3). The therapeutic strategy relies vastly on implant position. If the implant is within the bony housing, reconstructive therapy is indicated after comprehensive surface detoxification (Monje et al. 2022). Given that these defects are contained or partially contained, a volume-stable bone grafting material or a barrier membrane may favor graft stability. On the other hand, if the implant is outside of the bony housing, implantoplasty is advised for the area where the reparative potential is incomplete (see the combined therapy). For the intrabony component within the bony housing, reconstructive therapy is indicated (Monje & Schwarz, 2021). Repositioning of the flap is recommended, given that mucosal recession will spontaneously occur in the aspect where implantoplasty was performed. That, together with bone reconstruction in the intrabony component, would mediate the resolution of inflammation by reducing pocket depth. If, at the re-assessment, there is no or limited band of keratinized mucosa, it might be advisable to augment it by means of a free epithelialized graft.

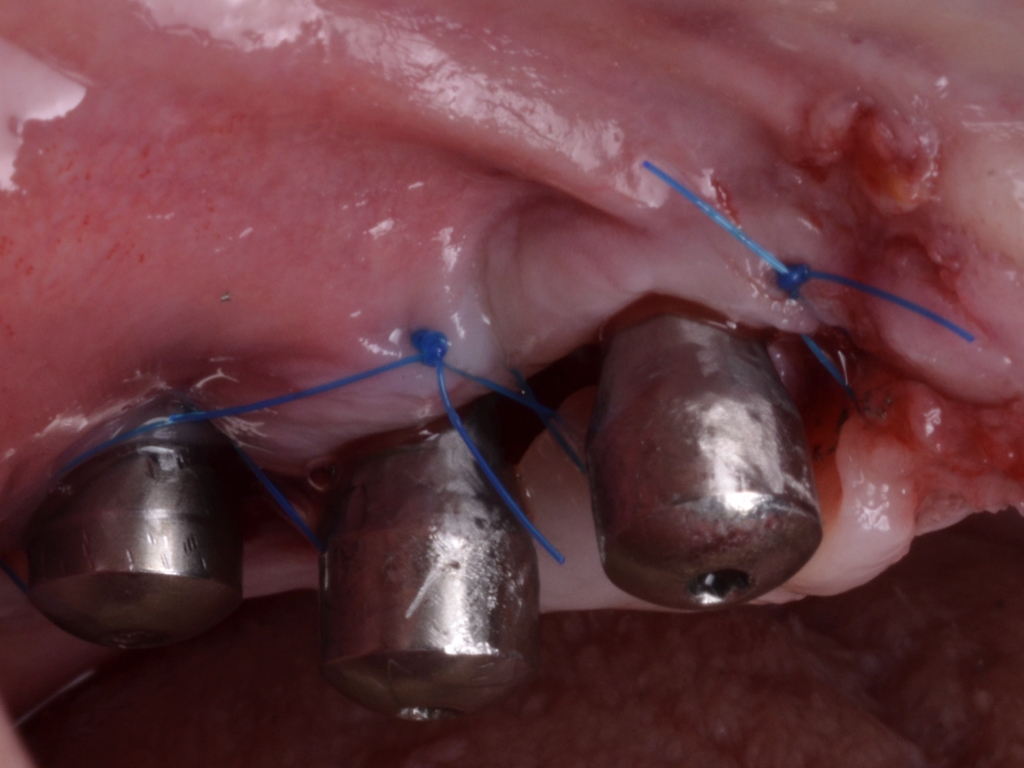

Combined therapy

A full-thickness flap must be elevated to access the defect. In the case of abundant KM, partial excision of the epithelium is recommended. Otherwise, an intra-sulcular incision must be performed with the goal of isolating the soft tissue lesion and leaving it attached to the implant and bone defect. The lesion must be removed using curettes. Implantoplasty is recommended for the supracrestal component, while surface decontamination strategies are to be applied in the intrabony compartment. If the implant is slightly outside the bony housing, implantoplasty would also be indicated for this aspect. This is the so-called combined therapy described initially elsewhere (Schwarz et al. 2011). Due to the nature of the defect, stabilizing bone fillers with a barrier membrane is encouraged. The flap must be apically positioned to reduce pocket depth. As a result, the polished surface will be exposed to the oral cavity.Again, if there is no or limited band of keratinized mucosa at the re-assessment, it might be advisable to augment it by means of a free epithelialized graft.

Conclusion

Surgical therapeutic strategies are proposed according to defect configuration to achieve clinical resolution of disease using flattening bone architecture. Further, it is critical to address local factors related to soft tissue characteristics and prosthesis design that contribute to disease initiation and may lead to recurrence. Adherence to a periodic supportive maintenance program is decisive for long-term stability.