Introduction

The ITI Treatment Guide Vol. 9 provided us with an innovative solution called the “back off” strategy for elderly patients (Müller & Barter 2016). However, patients’ conditions vary widely, and the details of how and when to back off are unknown. The purpose of this clinical report is to discuss the importance of the timing of intervention in the “back off” strategy.

When calculating the unhealthy period (the period of illness or disability) from the average life expectancy and healthy life expectancy in Japan, men spend about 8 years and women about 13 years in an unhealthy period. The first baby boomers are now over 75 years old, and, globally, elderly implant patients are entering the unhealthy period (Ohtsuka et al. 2018). How long can implant prosthetics remain in place for patients with compromised oral function during the unhealthy period? Will the superstructure need to be changed to an implant overdenture (IOD) for back-off? If so, when does it need to be prepared? For that matter, are there any instances when back-off should not be done?

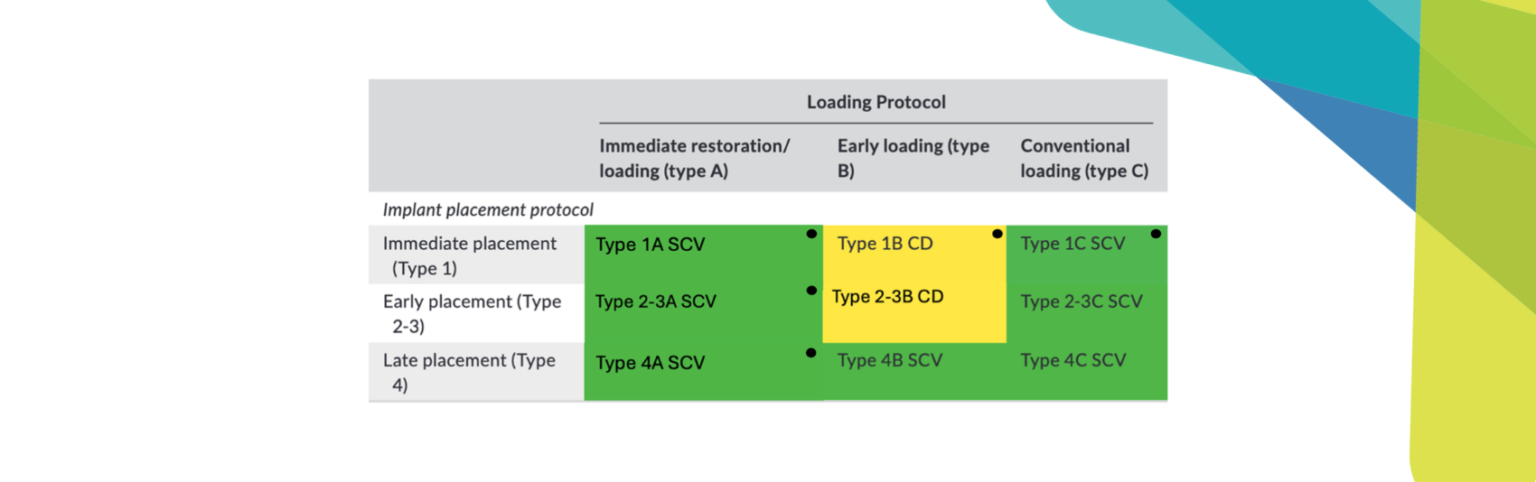

There are 4 phases in the unhealthy period (Fig. 1), and in each phase, the elderly will not only have oral hygiene problems but also problems ranging from dysphagia to undernutrition(Salvi et al. 2012). Weight loss is a significant problem in geriatric care and may even be an early sign of cognitive decline(Tamura et al. 2013). And then, in a dental strategy of oral intake in home dentistry, there are three elements: “cure” “care,” and “rehabilitation” (Suga et al. 2014). The needs of these elements change during each phase of the unhealthy period. For example, in the acute phase, which is directly linked to life and death, “care” aimed at reducing the number of bacteria is prioritized over dental treatment. During the recovery period, the elements of “cure” and “rehabilitation” become more important, because the oral function has to recover, leading to patient discharge and independence of life. After discharge, we provide “care” and “rehabilitation” to maintain a good oral environment and provide “cure” as needed (Fig. 1).

In the terminal phase, we contribute to the QOL of patients and their families with focusing on “care”. In this way, even in the phase when long-term care is needed, Dr. Suga recommends that the oral environment be adjusted, and dysphagia is recovered.

What is the role of dental implants in the final stages of life? How should we approach this? Two cases highlighting the unhealthy period will be presented as back-off cases, discussing what is important for patients in this phase.

Case 1 with back-off

A case in which rehabilitation progressed with back off

A 75-year-old woman (155 cm/46.7 kg/BMI 19.4) was emergency transferred to our hospital in 2016 for left thalamic hemorrhage and was treated by the Department of Neurosurgery and Rehabilitation Medicine. She was referred to our department to improve masticatory function by the nutritional support team (NST) in our hospital. The patient’s history included hypertension, scoliosis, right hemiparesis due to left thalamic hemorrhage (Japanese Certification Level 3 of Needed Long-Term Care), aphasia, dysarthria, and right paralysis in the orbicularis oculus, orbicularis oris muscle, and nasolabial folds. Tongue movement was normal, but the tongue was shifted to the right.

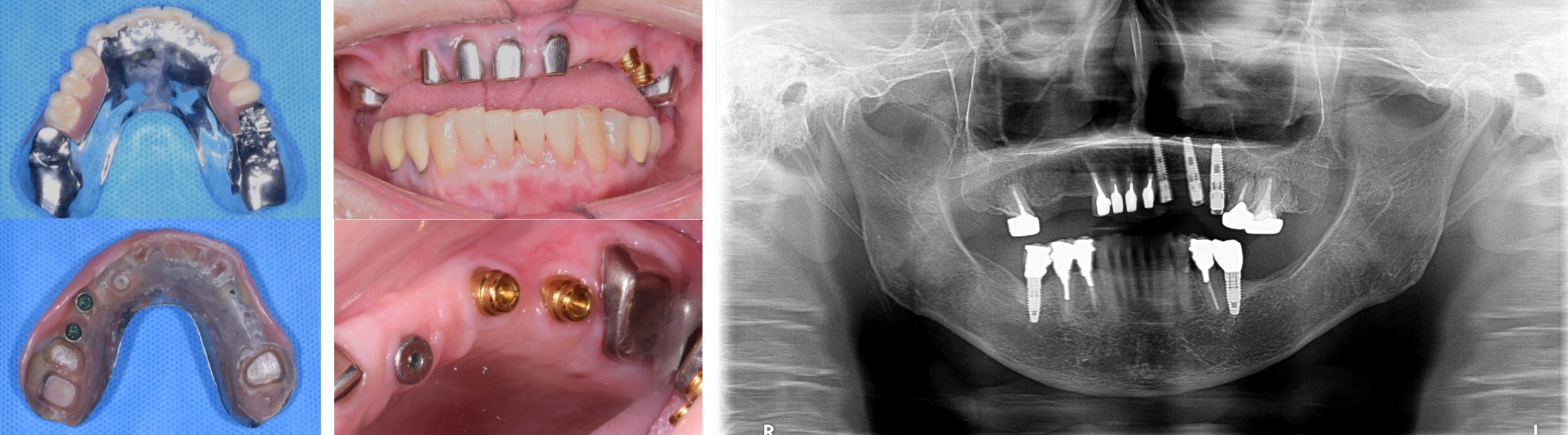

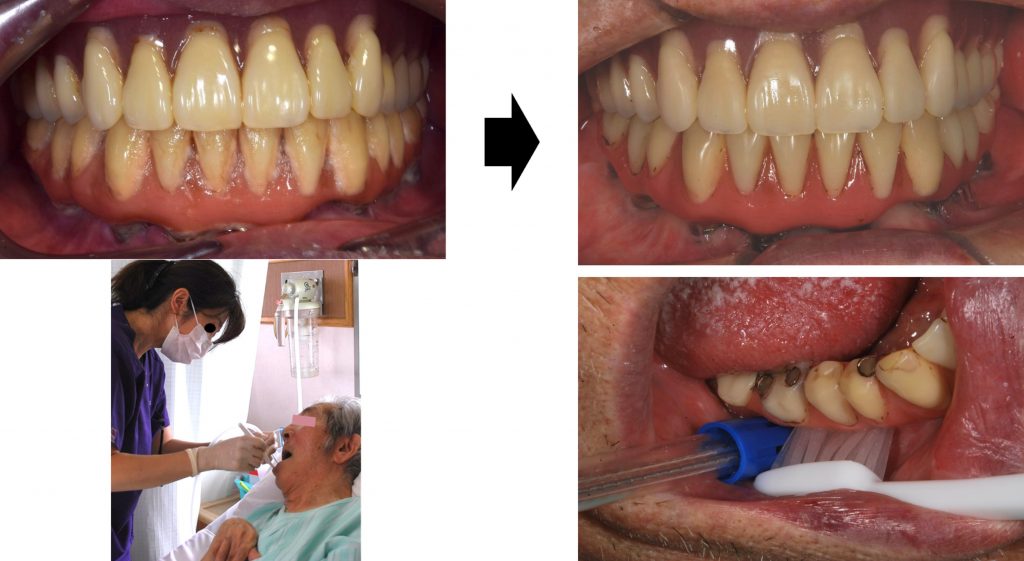

Implants in her mouth had been placed about 10 years earlier and had already been backed off from a fixed prosthesis to a removable prosthesis (Fig. 2a).

Nevertheless, the problem was that she was unable to remove the denture by herself due to loss of mobility in her dominant right hand and the associated difficulty in cleaning the delicate area around the attachment. The patient first had to learn how to use her healthy left hand for this. The attachment was a LOCATOR® (Zest Anchors, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and the retentive force had been temporarily lowered from blue (0.68 kgf) to red (0.45 kgf) for handling the IOD (Müller & Schimmel 2016; Müller 2018; Srinivasan et al. 2017). Indirect and direct training for dysphagia rehabilitation were provided together with speech therapy (ST), while dental training was also provided. At the same time, she continued to receive independent oral care and denture removal training as dental training. The back-off strategy for both the superstructure and the attachments facilitated oral rehabilitation, and she made good progress with her dysphagia. Now, she has recovered from her speech disorder and dysphonia, and she is independent and progressing well as relates to her implants, remaining teeth, denture function, and hygiene (Figs 2b – c).

Case 2 without back-off

A case of suspected low nutrition

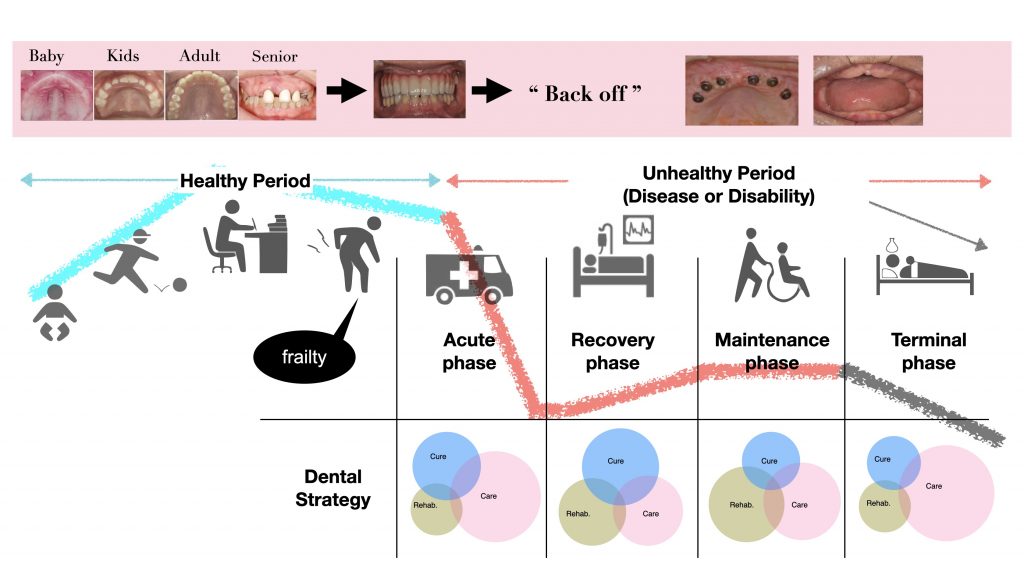

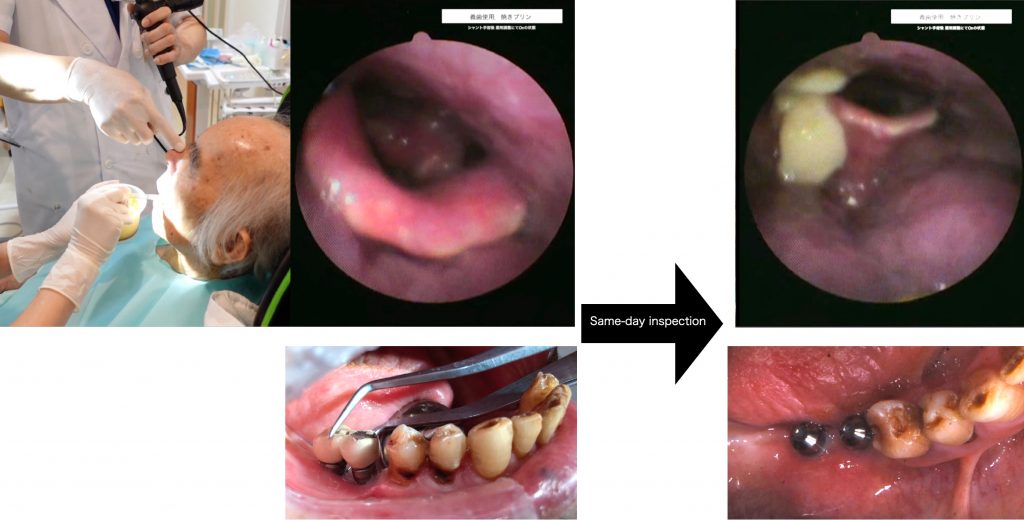

An 88-year-old man (170 cm/51.1 kg/BMI 17.8) with atherothrombotic cerebral infarction and Parkinson’s disease with severe functional impairment (degree of care required and medical necessity: AO B10) was admitted in 2015 for treatment at the Department of Neurosurgery and Rehabilitation Medicine. The family requested professional oral hygiene management regarding his dental implants, and he was referred to our department. The patient had a history of hydrocephalus shunt surgery and was diagnosed with right-sided paralysis, dysarthria, and severe dysphagia (oral diadochokinesis revealed /p/: poor lip closure, /t/: inaccurate articulation of the tongue apex, significant distortion, /k/: tongue not elevated, pharyngeal retention heard, high risk of aspiration). At the time of dental intervention, he was transitioning from acute care to convalescent rehabilitation; a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) was placed, and oral intake training was started at the same time. Plaque control of the bone-anchored bridge by the caregiver was poor and required professional hygiene management (Fig. 3).

There are two key points:

- It is necessary to prevent malnutrition in patients (Tamura et al. 2013)

- Dental intervention is difficult at a time when the patient’s ability to receive dental treatment is decreasing (Müller & Barter 2016; Risen et al. 2014; Suga et al. 2014)

In other words, backing off the bone-anchored bridge that is familiar to the perioral tissue is a significant risk. The patient was not able to take the required amount of nutrition by oral intake alone and was undergoing dysphagia rehabilitation while receiving nutrition by PEG. Changes in the oral environment, such as unfamiliar dentures and the sudden loss of occlusion, are predicted to cause functional decline in the preparatory phase (mastication), which may follow low nutrition(Luraschi et al. 2013).

If the oral environment can be maintained with the support of family and caregivers, implant fixed prosthesis may be more beneficial for dysphagia. This is because the mandible is the starting point of the maxillary digastric muscles, which are necessary not only for the preparatory stage of mastication but also for swallowing, and without vertical stop, the jaw position becomes unstable, resulting in insufficient or delayed elevation of the hyoid and larynx, which may cause aspiration in some cases. In the past, we have experienced cases in which a sudden loss of molars caused a residue in the pharynx (Fig. 4).

Rehabilitation was carried out without removing the fixed prosthetic dentures, and now the patient is able to take oral nutrition without PEG. His meal pattern has also improved to a chopped meal. His implant care is also progressing well and functioning well with the cooperation of his family.

Discussion

How long can the implant superstructure be kept in place for a patient with declining oral function after a healthy life span?

As a precondition, it is possible to keep the superstructure in the mouth if seamless oral care and oral rehabilitation are available (Srinivasan et al. 2017). However, the fact that the superstructure can be kept does not mean that the dysphagia function can be maintained (Bradbury et al. 2006).What we can do in the healthy period to ensure the long-term function of the implant superstructure is, when planning the implant treatment, to keep in mind what will happen when the patient is no longer able to visit the clinic. In other words, considering that the superstructure will need to be remanufactured in 20 to 30 years, a screw-fixed superstructure that takes back-off into consideration should be discussed (Müller & Schimmel 2016). It is also important to prevent oral frailty by designing a superstructure that allows not only self-care but also oral care by family members and caregivers, along with regular checkups and cleaning instructions to prevent complications as well as advice about healthy diet.

This approach to planning the implant treatment and enhancement of post-treatment maintenance may make the implant superstructure useful for the recovery of oral function and the rehabilitation of dysphagia if the patient becomes unhealthy.

Is it necessary to change the superstructure to an IOD for back-off?

It is not necessary to change to a removable superstructure, but rather the design should be modified to make it easier for family members and caregivers to assist with oral care, which will ensure oral hygiene for a longer period of time, even with a fixed superstructure. In addition, low nutrition in the elderly is an important problem (Müller & Schimmel 2016), and careful consideration should be given to avoiding it.

If so, when should changes be made?

Essentially, the most appropriate time to change to a removable denture is during the initial treatment planning stage or superstructure reconstruction stage during the healthy phase. In the unhealthy period, dental care is almost never possible during the acute (emergency) phase, and oral care is the main focus (Salvi et al. 2012; Suga et al. 2014). Treatment may be possible in the recovery and maintenance phases, but treatment in the unhealthy period is more complicated because dental treatment itself is more difficult, and nutritional problems as well as systemic disease management are involved.

What is the role of dental implants in the final stages of life?

It is very similar to the purpose of oral rehabilitation – to enable eating, speaking, and regaining oral health.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses her sincere thanks to Prof. Chikahiro Okubo for carefully proofreading the manuscript. I also thank Dr. Ryohei Iida, the visiting dentistry specialist, Prof. Chie Yanai (Study Club Coordinator of the ITI Section Japan) and Dr. Mihoko Atsumi (Director of the ITI Study Club Diversity Tokyo) for commenting on this report.